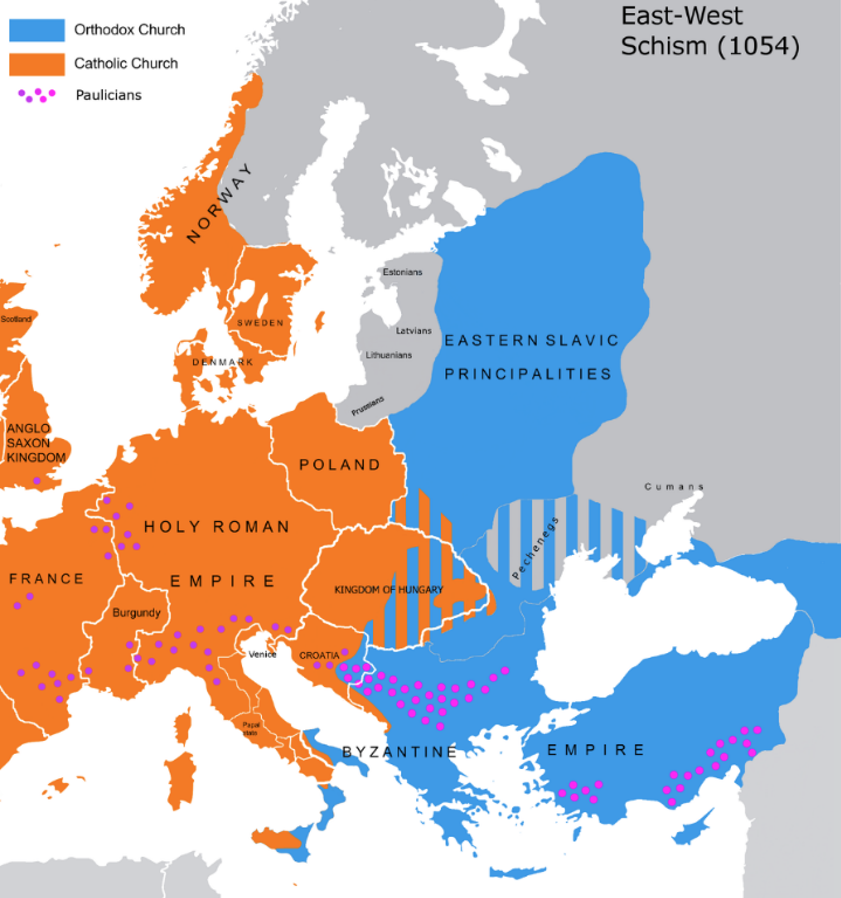

Religious wars and competition for religious supremacy that allowed feudal medieval Church to oppress people while some Church leaders were openly corrupt, led to an open call by Christians to return to original apostolic Christianity. The Roman and Byzantine Churches reacted to their critics with severe punishment, and/or forced conversion. There was a need to re-evaluate Christianity as it has evolved in the institutional Christian Church.

On the one hand, various religious movements developed independently to serve the needs for the poor and oppressed, and on another, various spiritual movements inspired by renewed interest in the interpretation of the Bible, particularly the Book of Revelation, study of the ancient Greek and Roman myths and religions, and the works of the early Church Fathers.

The literal understanding of the biblical writing, which created belief in witches, devils and all kinds of spiritual manifestations, the cruelties by the Turkish invasions, and increased antisemitisms led some intellectuals to search for a universal religion based on common human values and aspirations.

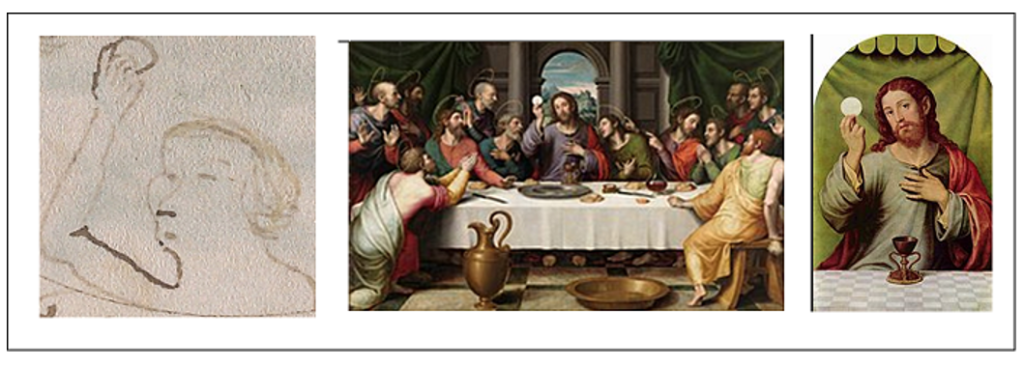

Because Jesus’ teaching is so universal, it could be applied to different situation and explained in the symbols that Jesus used, like Sun, grape-wine etc. The humanists understood Jesus’ primary concern was for people, for individuals to be able to think for themselves and find the Truth by themselves, as he did, and stand for it, so that the entire society can benefit and eventually evolve to a more just society.

The religious superstition caused by worshipping the relics and religious objects, like the wounds of Christ, did not contribute to better understanding of Jesus’ teaching. On the contrary, it was causing religious fanatism.

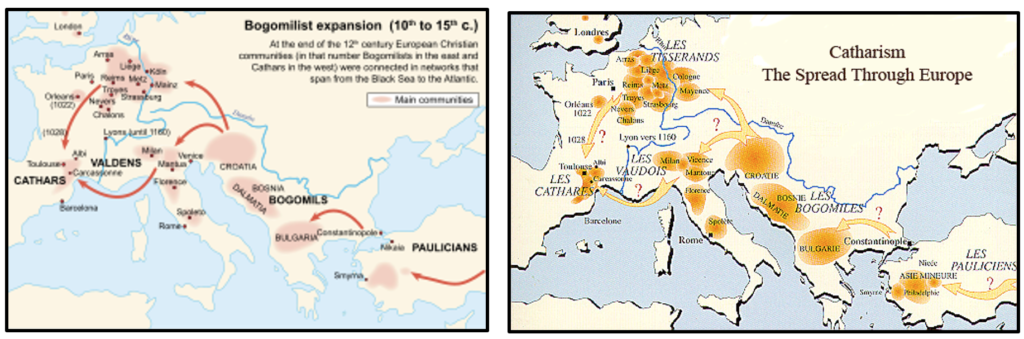

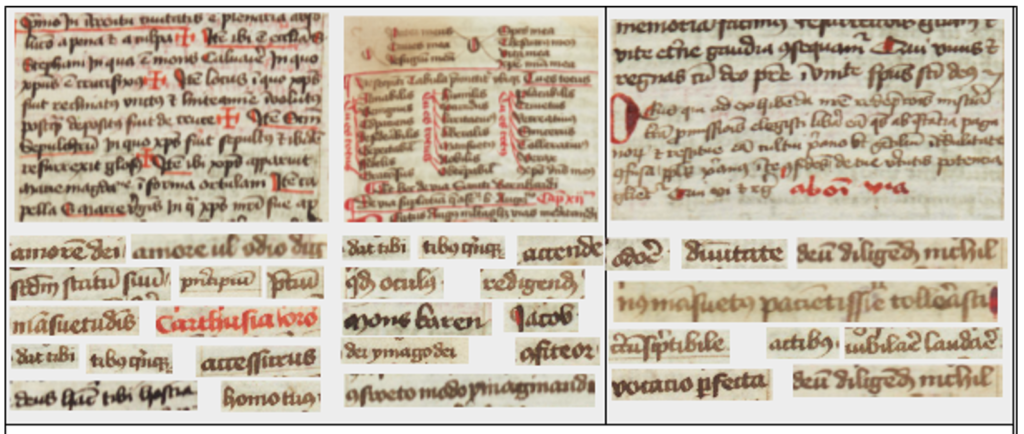

The medieval humanists recognized that Christianity has degenerated when the Church allied with the feudal imperialistic rulers, so that drastic reforms were needed. To do so, the humanists had to go back to the source, to examine what was wrong with the Old Testament and where Christianity had strayed away from the original teaching of Jesus. For genuine Christians, it was hard to comprehand that God, who was pure Love, would approve of forceful conversions, crusades against pagans, burning of witches and critics of the Church. They saw the solution by writing in codded messages, so that only like-minded intellectuals could understand, and by promoting the reading of the biblical books and for this purpose, also promoting the schools, like the 10th century Bogomils and Cathars had been doing.

The Renaissance humanism started in Italy from where it spread across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. As the name suggests, humanists were the teachers and students of the humanities, which included grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. Some teaching came from Greece, and some from the Arabs. Latin scholars began studying Greek and Arabic works on natural science, philosophy and mathematics.

As a cultural movement, the Renaissance promoted Latin and vernacular literatures. The Renaissance began in the Republic of Florence with the writing of Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) and Petrarch (1304-1374). Other major centres were Venice, Genoa, Milan, Bologna, Rome, Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Antwerp.

The neo-Platonic humanists did not reject Christianity, but tried to present it in a new way.

Petrarch, who was a cleric, was first to encourage the study of pagan civilizations and classical moral virtues in order to preserve Christianity.

The Neo-Platonists were trying to reconcile Platonism with Christianity. They were followers of Saint Augustine. Neo-Platonism and Hermeticism, proponents of which were Nicholas of Kues, Giordano Bruno, Pico della Mirandola, among others, was popular trend that had great influence on Nicholas Kempf. Their ideas at times seem like a new religion.

I suppose the iconoclastic Humanism was regarded Godless. Not worshipping icons was considered not respecting God. This does not mean that the adherents were godless, only that they worshipped what the sacramental symbols represent.

Esoteric language is one of the safeguards placed in the Bible to assure humanity that the universal values Jesus promoted, would continue in all cultures, all times and in all places, even if the Church becomes so corrupt that people stray away.

We are forgetting that many saints were persecuted by the same Church that later beatified them. This happened to many Christian mystics.

This situation may be generalized to include any religion of any time and place. Every religious movement begins as a humanistic movement, with the wellbeing of humanity as the primary goal. Eventually the entire society gets corrupted, which can cause the fall of civilisation.

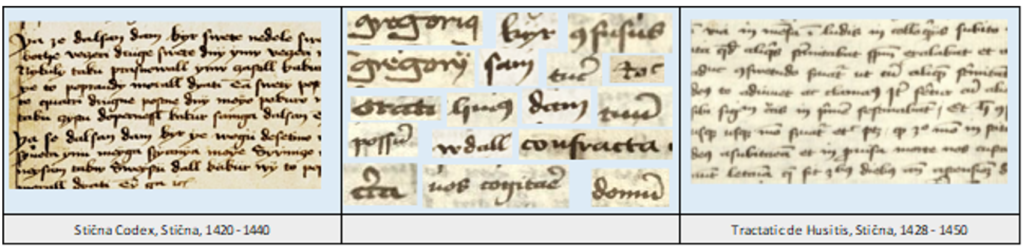

Early Slovenian Humanist

Slovenian history has been wrapped in mystery because the German historians simply counted them among Austrian (or German) scholars and dignitaries, because the political situation required that they speak German and Latin. Also, since their land was occupied by Germans, they were counted as Germans. However, their distinct Slovenian names, either Latinized or Germanized, at times even the pseudonyms, reveal their Slovenian origin, although some also originated from German noble families.

Nicholas Kempf was not Slovenian by birth, but he spent over 30 years in Slovenian speaking environment. He studied humanities at Vienna University, where at the time of his studies, at least seven professors were of Slovenian origin. Dennis Martin, who wrote Kemp’s biography, does not mention Kempf’s association with Slovenians, nor the fact that many Slovenian professors who studied at Padua University, spread humanism at the Vienna University. Martin mentions some Neo-Platonists that inspired Kempf, such as Gerson, Nicholas of Kusa.

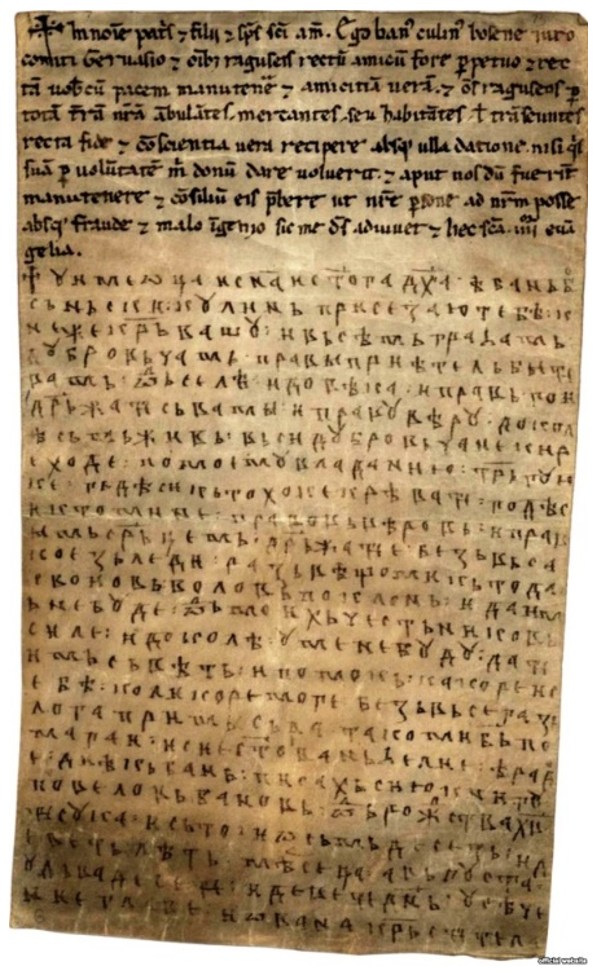

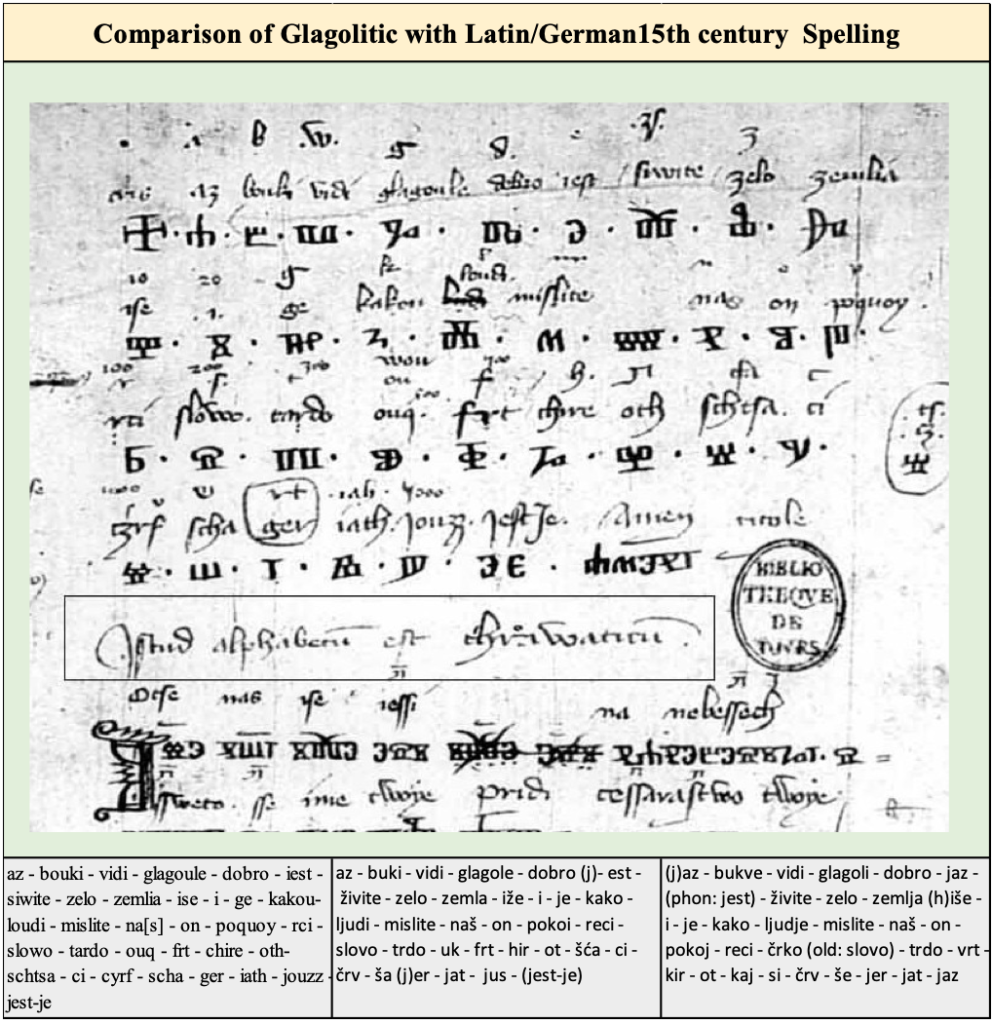

Before Kempf came to Dolenjska and Štajerska, Glagolitic writing was used, as it is attested by Georgius de Sclavonia, native of Brežice (Slovenia). He learned glagolitic writing from Croatian priests before he went to study at Vienna University. In 1400, he wrote a book in Glagolitic and three years later, he obtained the doctoral degree. He later became profesor of Theology at the Paris Univesity. He left many theological works, among them the Mns. 95, containing several texts in Cyrilic and Glagolitic.

From his writing, it is also clear how religion played into politics. In a similar way the Germans used religion to Germanize Slovenians, the Croatians used Glagolitza and Croatian language in liturgy. Although both Slovenians and Croatians were part of the Patriarhate of Aquileia, Croatians claimed regions using Glagolitic as their territory. Gregorius’s statement Istria eadem patria Chrawati (Istria is a homeland of the Croats) was used by the Croats to obtain the entire Istria after WW2.

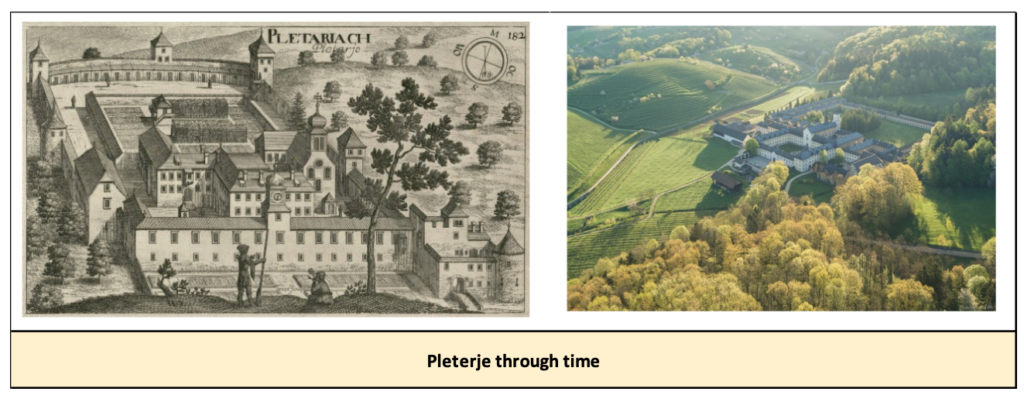

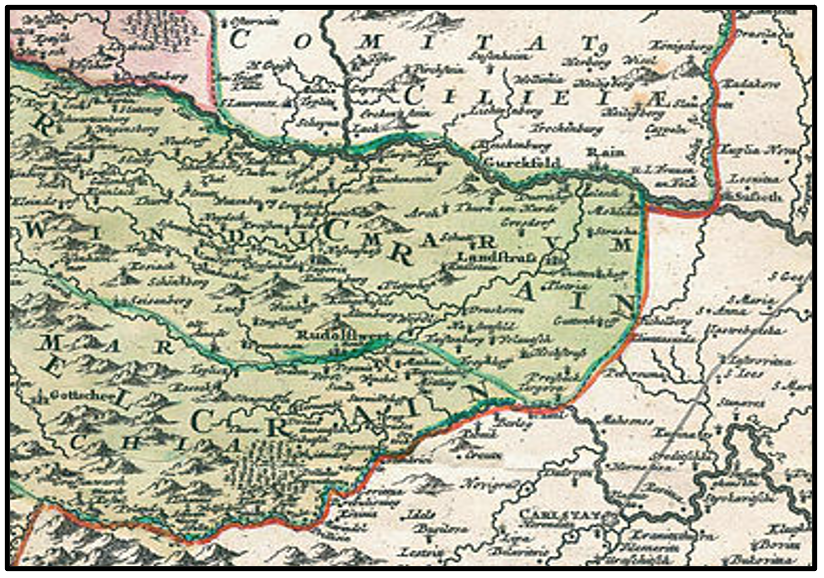

The Croatians proudly claim Georgius de Sclavonia for their scholar, although he was born in Brežice, which at the time was Slovenian teritorry (within a walking distance to Pleterje Charterhouse). Slovenians at the time had no king of their own; their territory was divided among Austria, Hungary and Italy. The designation ‘Slovenian’ did not include the citizens of the Kingdom of Croatia, but people who spoke Slovenian language, and who were called Winds or Wends by Germans. Even those territories where Slovenians lived under Habsburgs, were divided into different duchies, like Carinthia, Carniola, and marches, like Windish Mark, and Mark of Soune.

Although the Latin word for Wends/Winds was Slauone, the regional designations were used, like Carniolan, Carinthian. In 1415, when Carthusians formed the Fraternity of four Slovenian Charterhouses, they included Žiče and Jurklošter in the Duchy of Styria, Pleterje and Kostanjevica in the Duchy of Carniola.

No Carthusian Charterhouses from Croatia were included (they did not even exist), which is suggestive that the Carthusians were well aware of the distinction between Slovenians and Croatians.

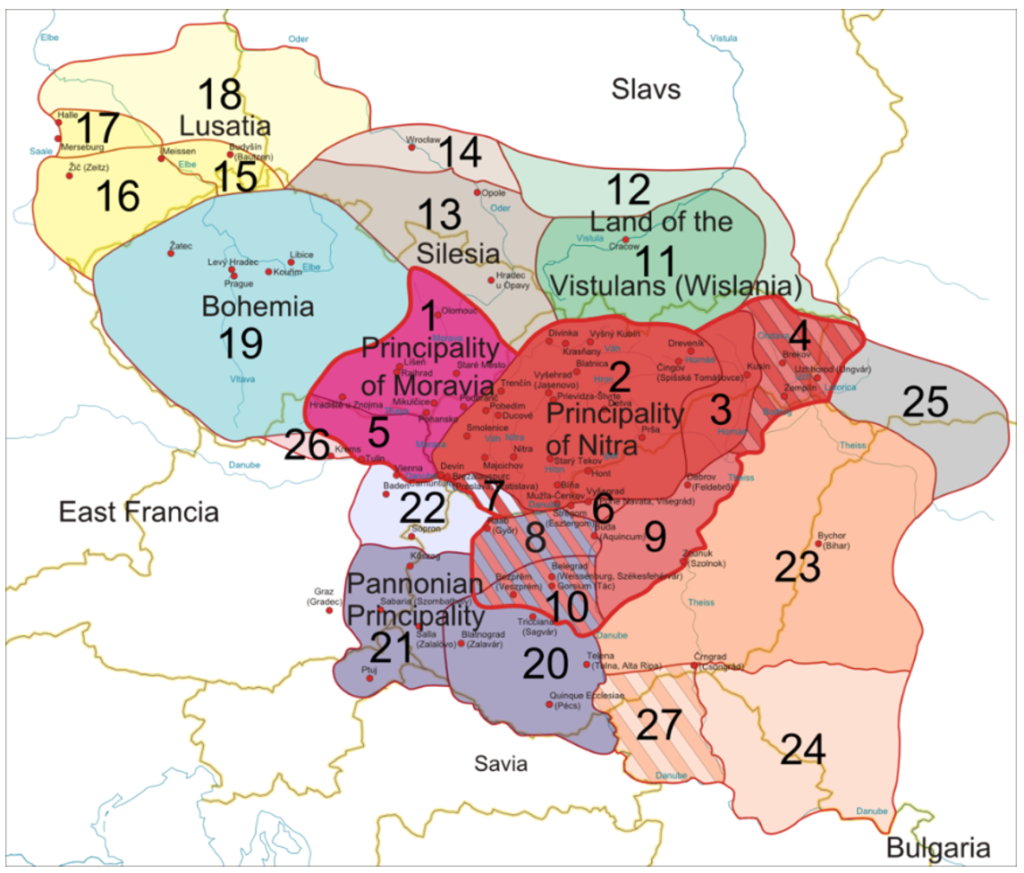

In the pre-Roman times, the inhabitants of Illyria, Pannonia and Dalmatia, spoke similar language which later became known as ‘sclavonic’, after Jordanes pointed out that Veneti, Antes and Sclaveni were the same people. In the mid-15th century, the Counts of Celje were the bans (rulers) of Sclavonia and large part of present day Croatia. The Kajkavian language, registered as one of the Croatian languages, is recognized by the linguists to have closer affinity to Slovenian, than to Croatian language. This can explain the similarity of Slovenian and Croatian language in the mid-15th century.

The Bosnian Bogomils used Glagolica, like Croatians. A lot of apocriphal and gnostic books were only translated in Glagolitic script, and they would naturaly be of interest of the humanists.

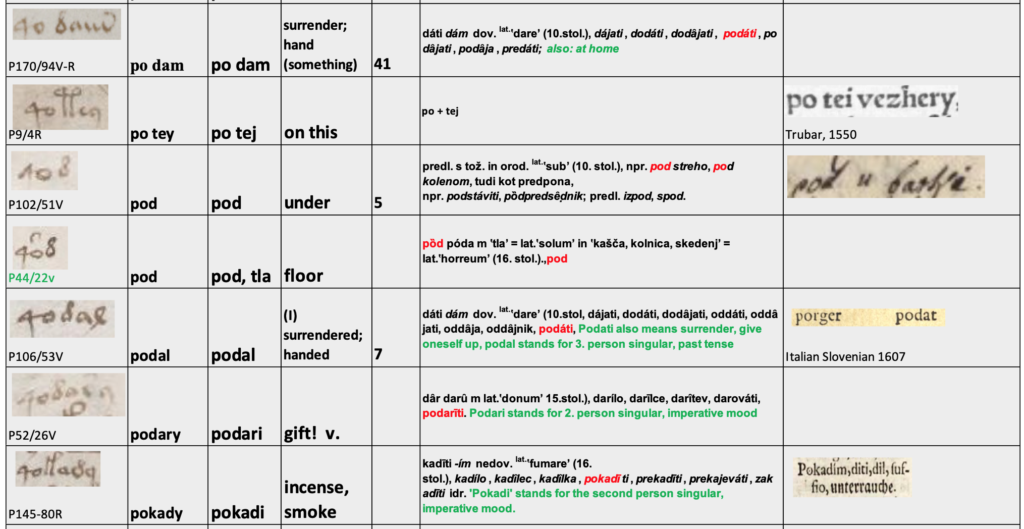

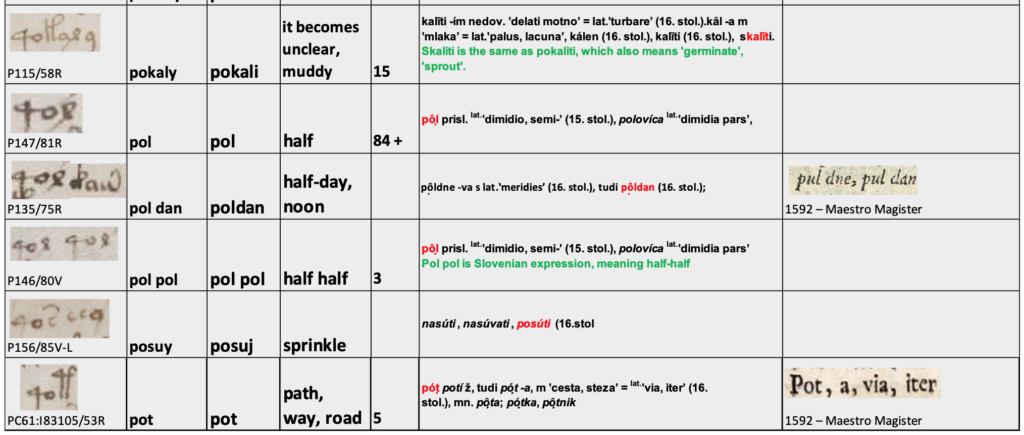

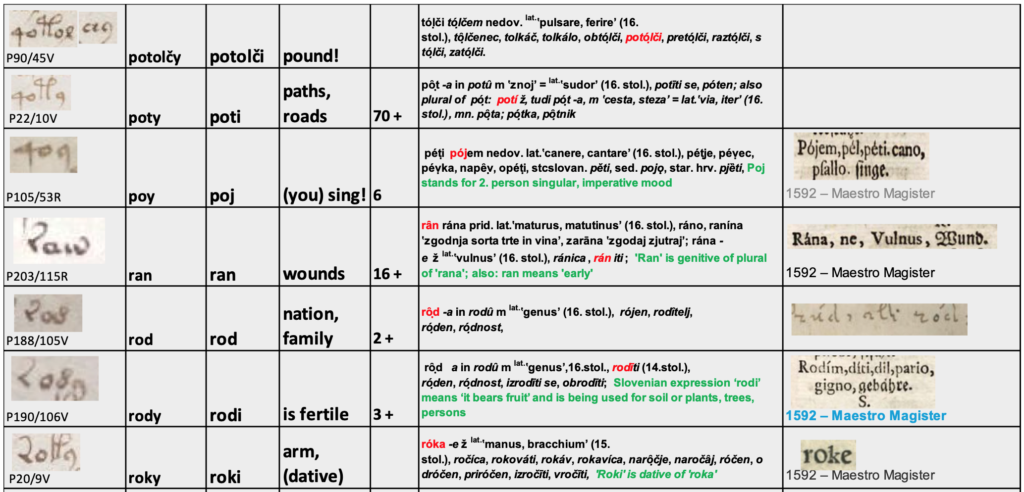

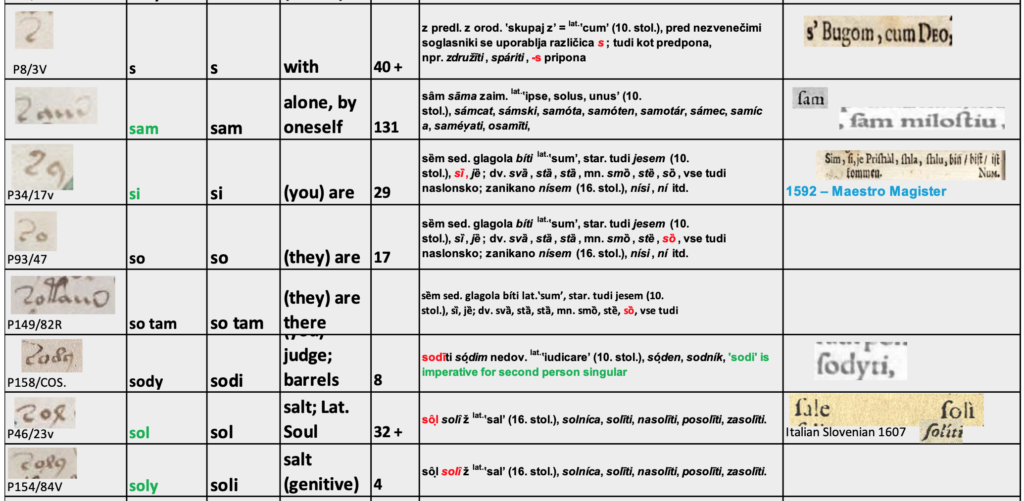

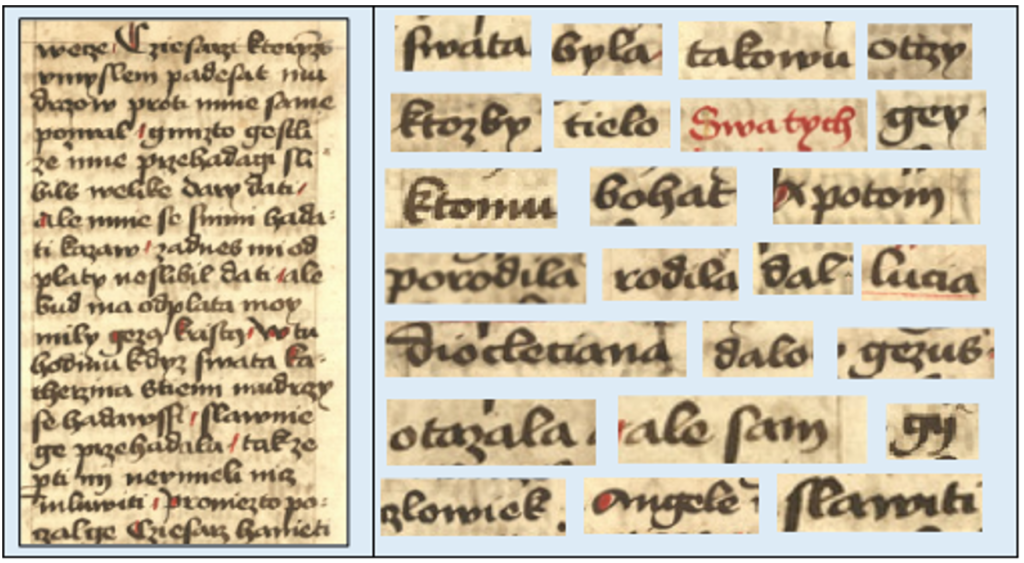

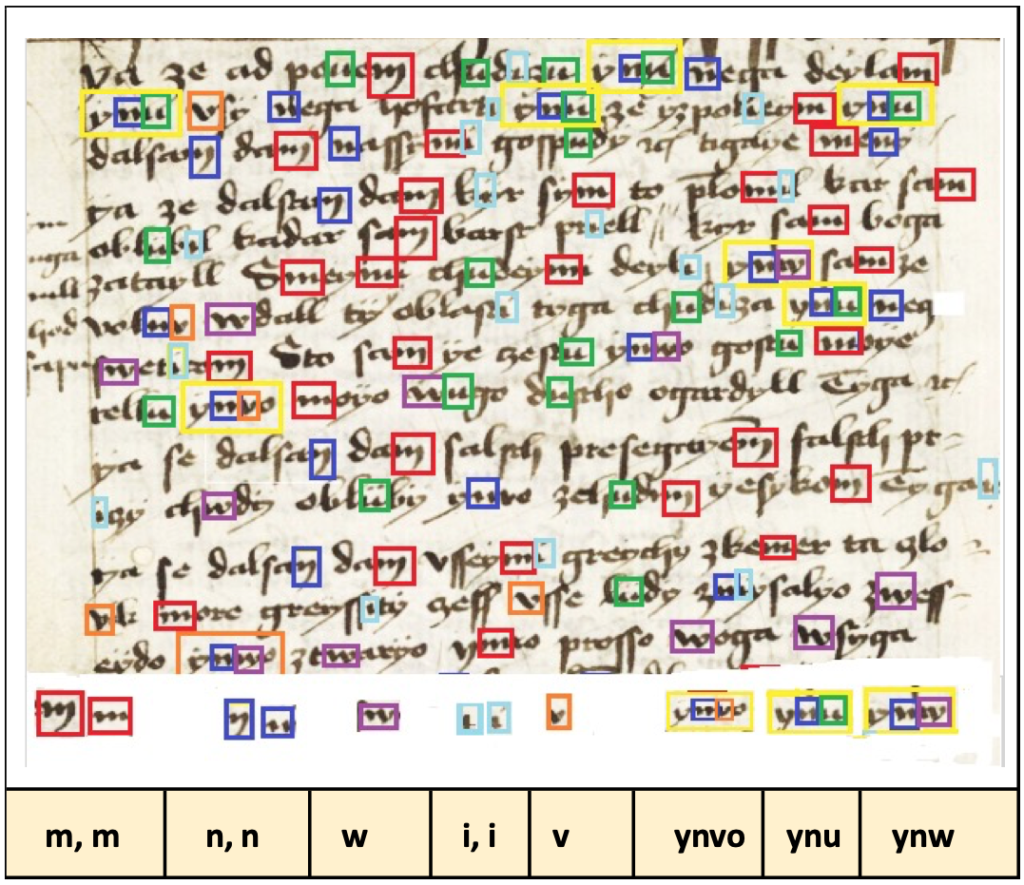

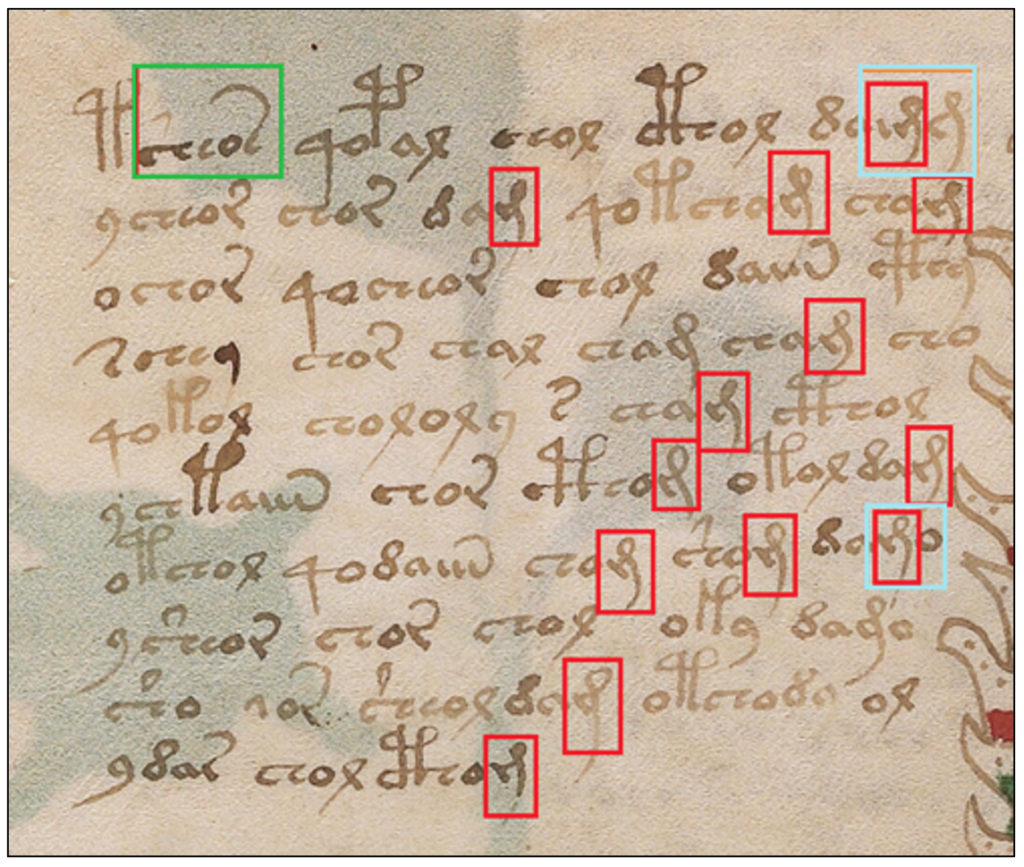

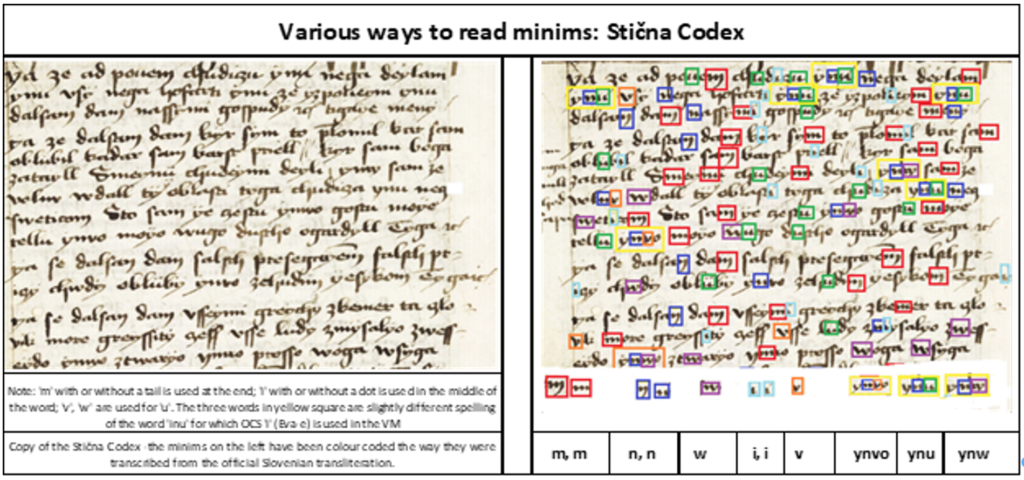

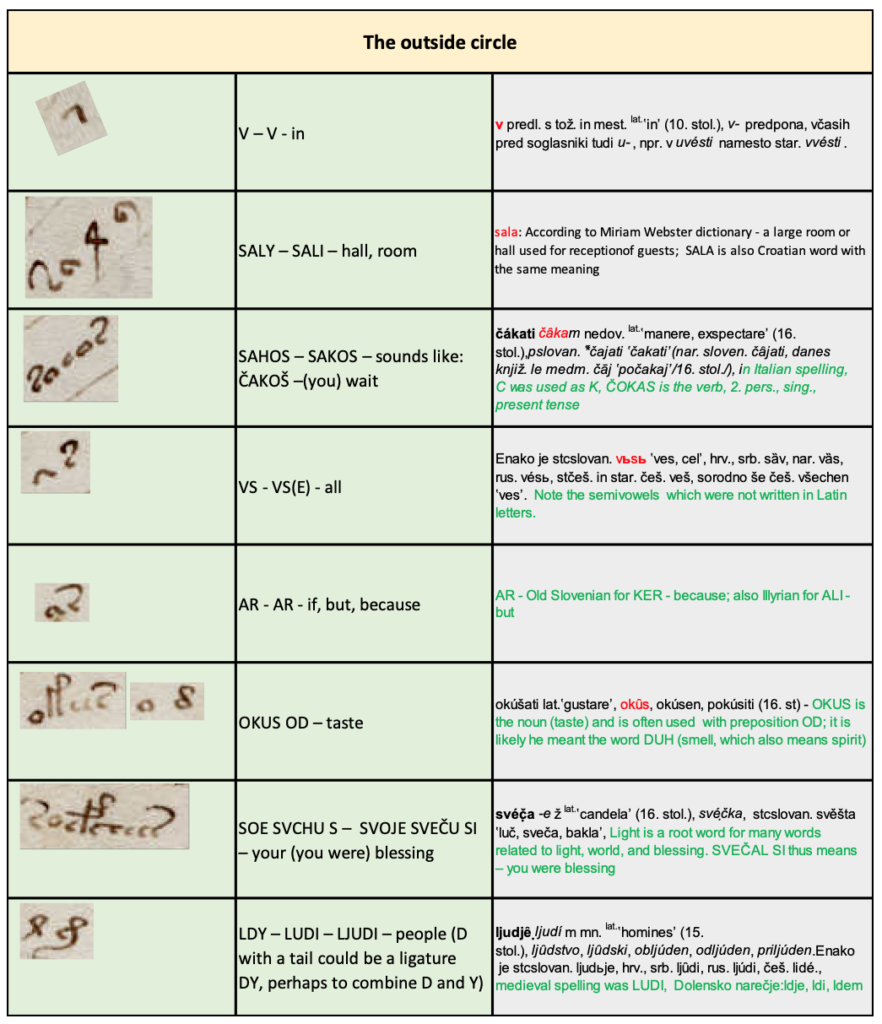

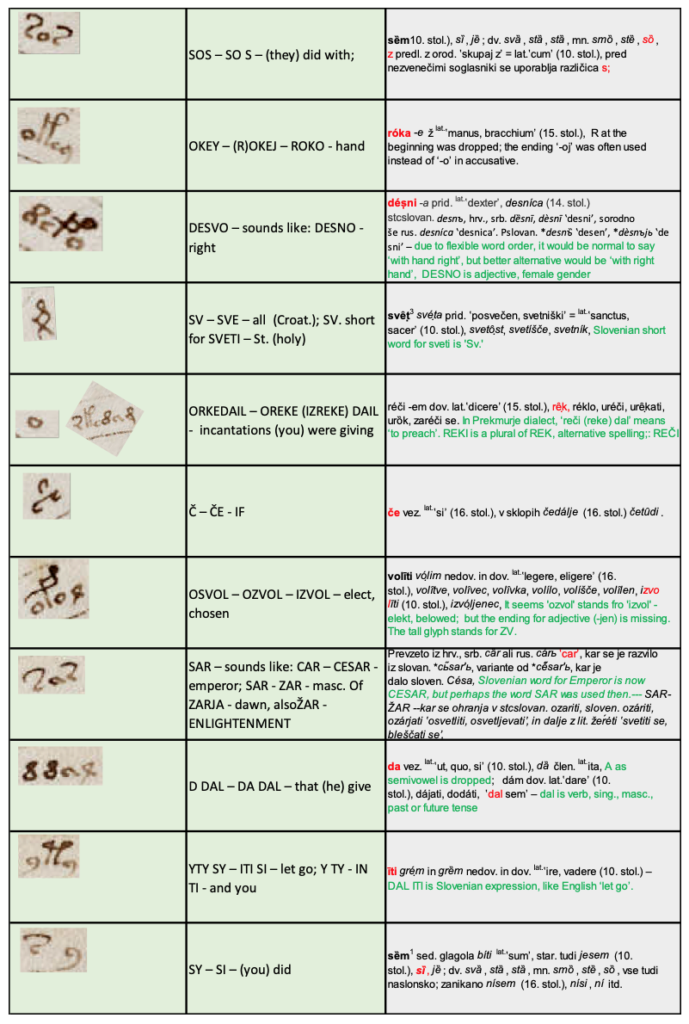

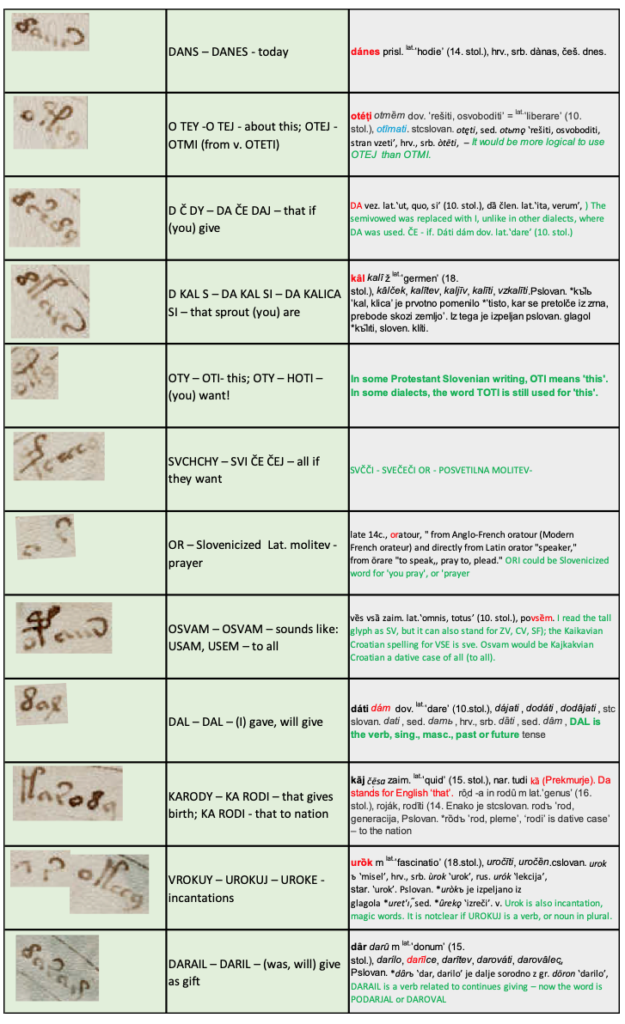

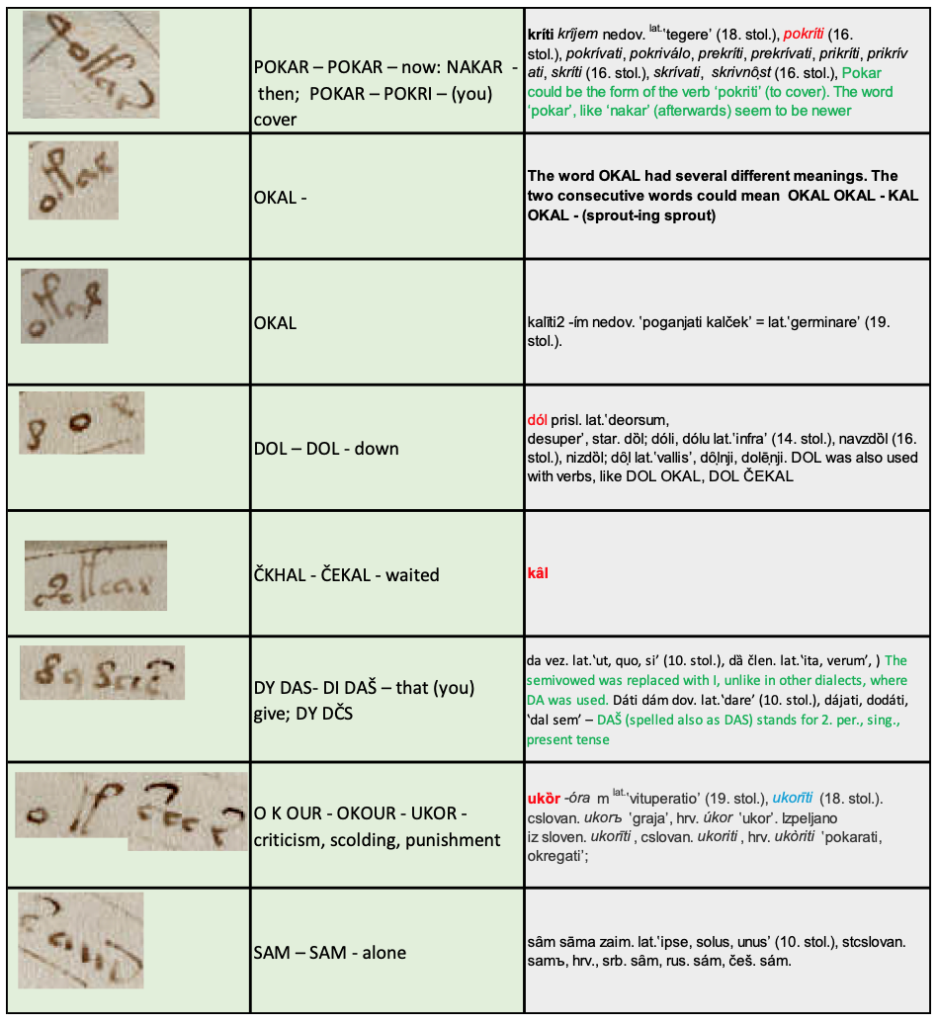

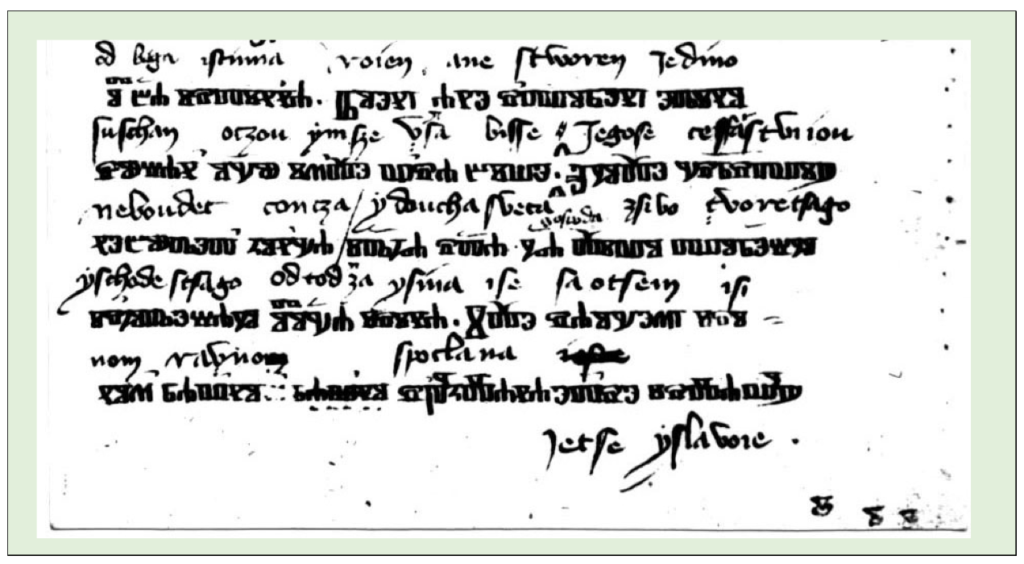

At the bottom: transcription of his handwriting (left), Croatian translation (middle), Slovenian translation (right)

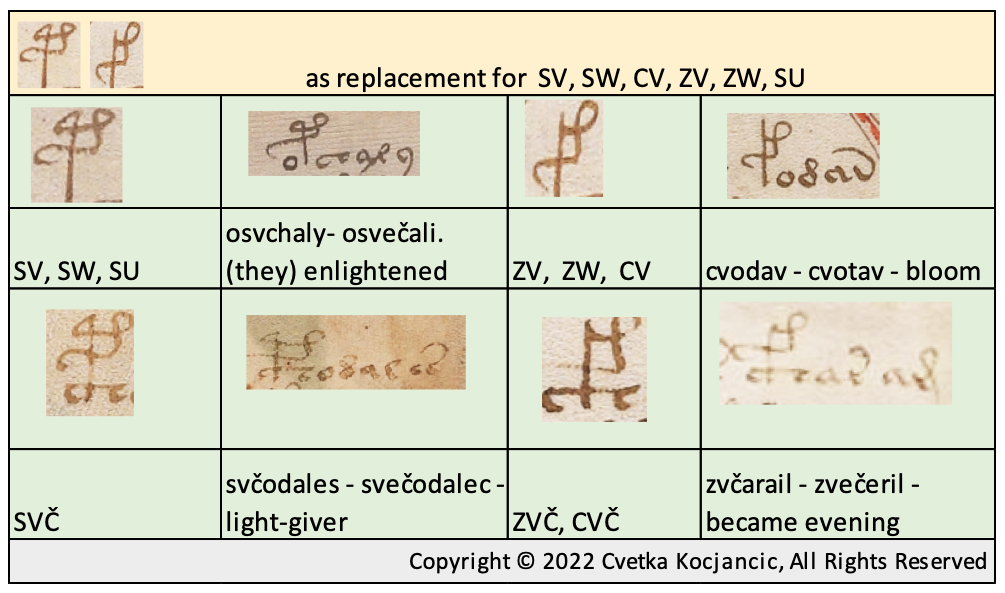

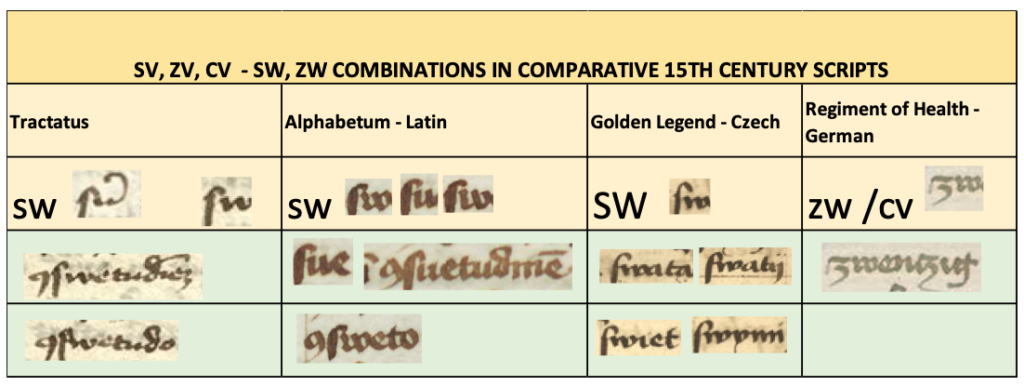

The above picture is a page from his Glagolitic book in which Georgius explains the letters of the alphabet. It illustrates how close Slovenian and Croatian were at the time and how little those basic words changed since the 15th century.

These Glagolitic notes were written while he was studying at the Vienna University, that is, before 1400, when he obtained the doctoral degree. This means that he would still be remembered at the University at the time Kempf was a student there, even if he was teaching in Paris at the time. There is also a question why he needed to write a Glagolitic book at the German speaking university, which had no designation for Slavic students.

Georgius would have learned Glagolitic at the time of Emperor Charles IV, who was very tolerant of Slavonic liturgy and Glagolitic script; he even promoted the re-introduction of Glagolitic in Bohemia, and in his proclamation, he ordered Princes Palatine to learn Slavonic language.

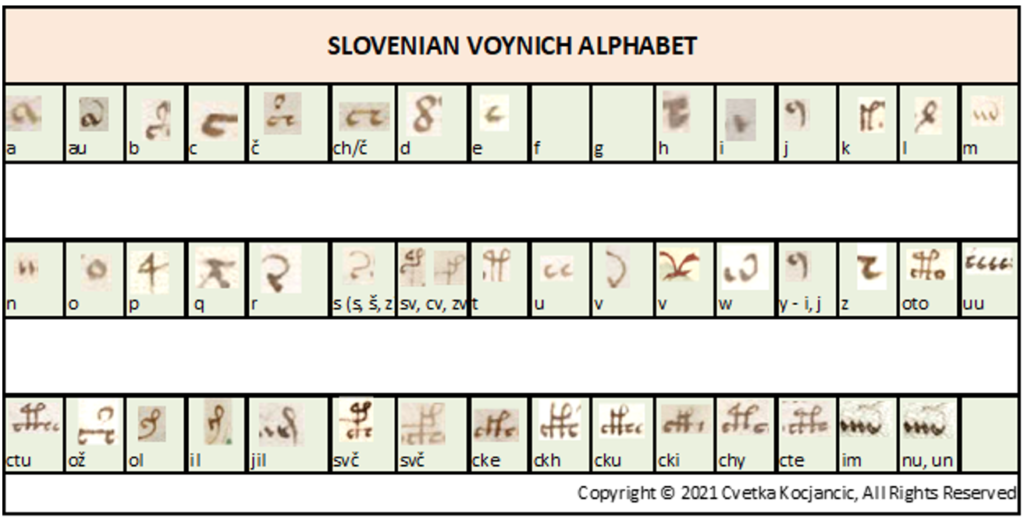

Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that Slovenians close to Croatia would use Glagolitic script to write down OCS language.

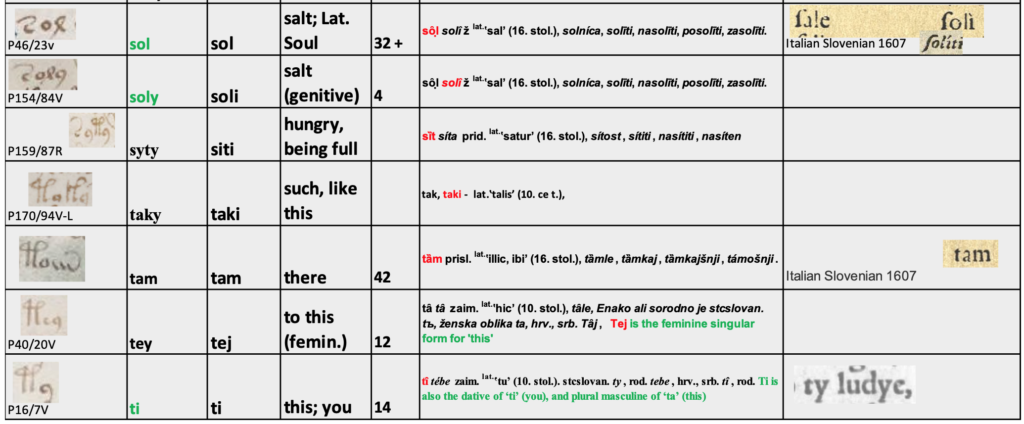

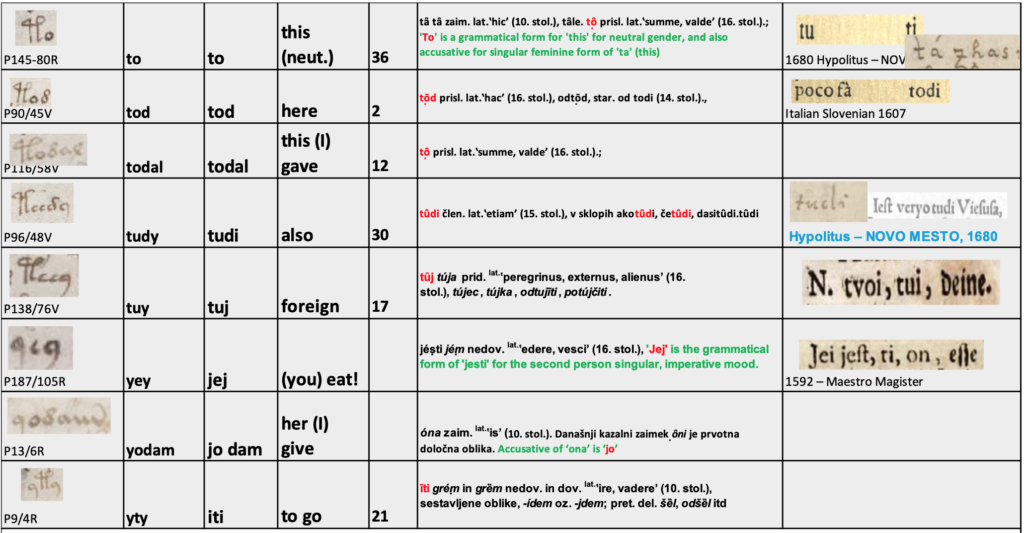

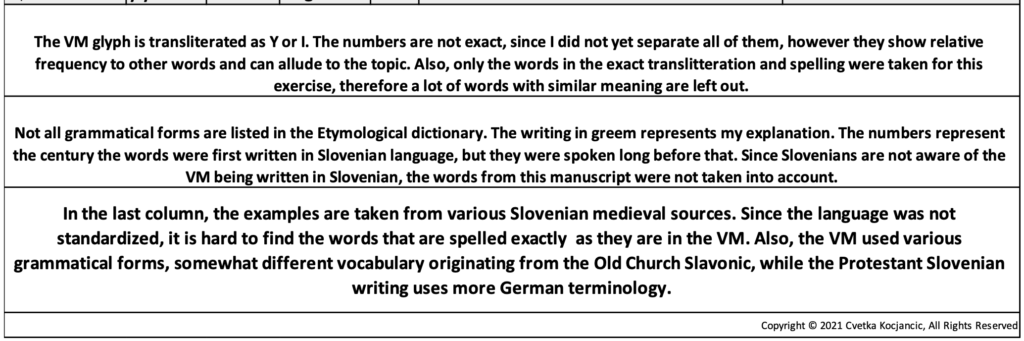

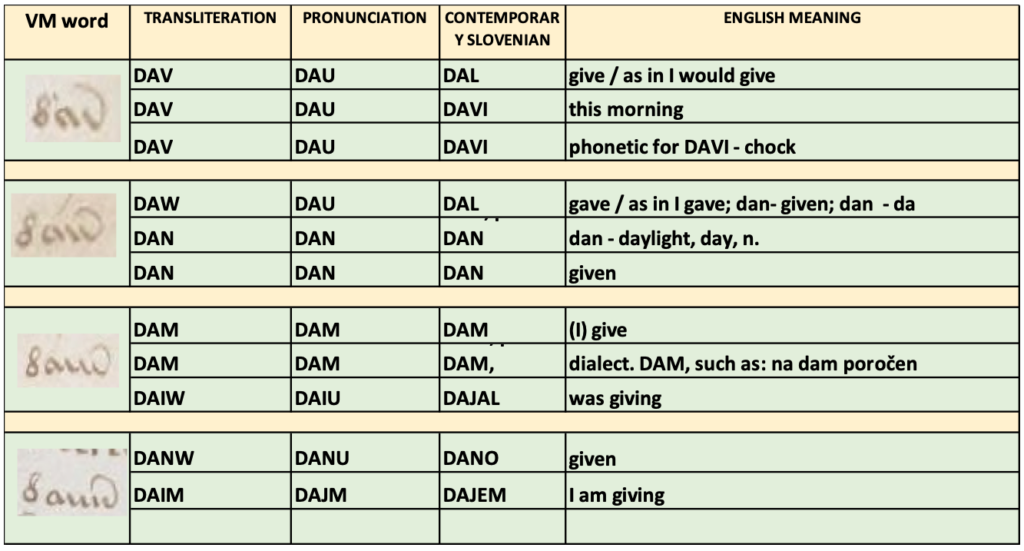

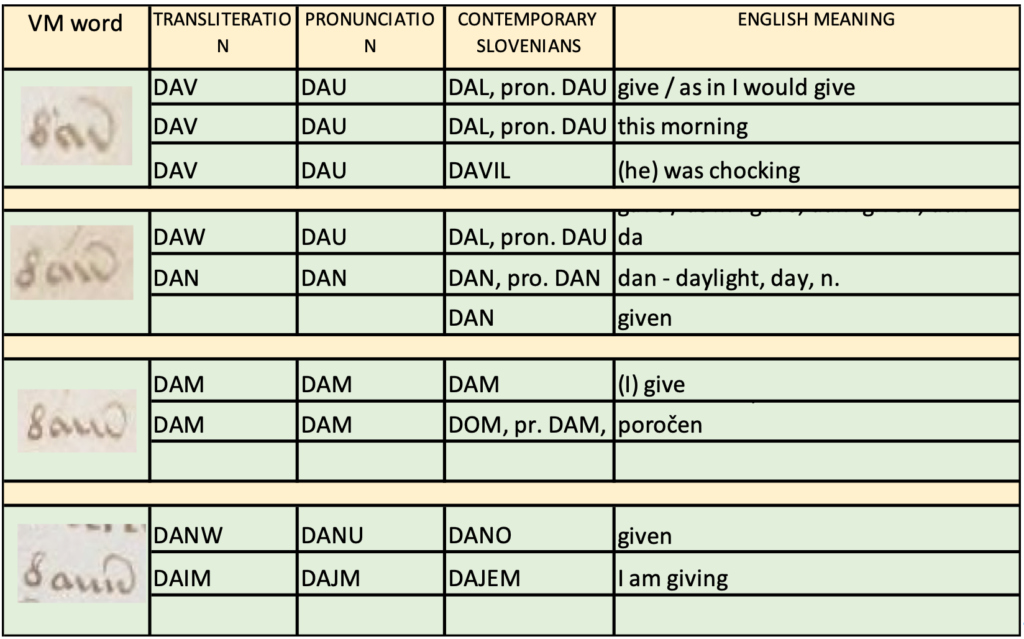

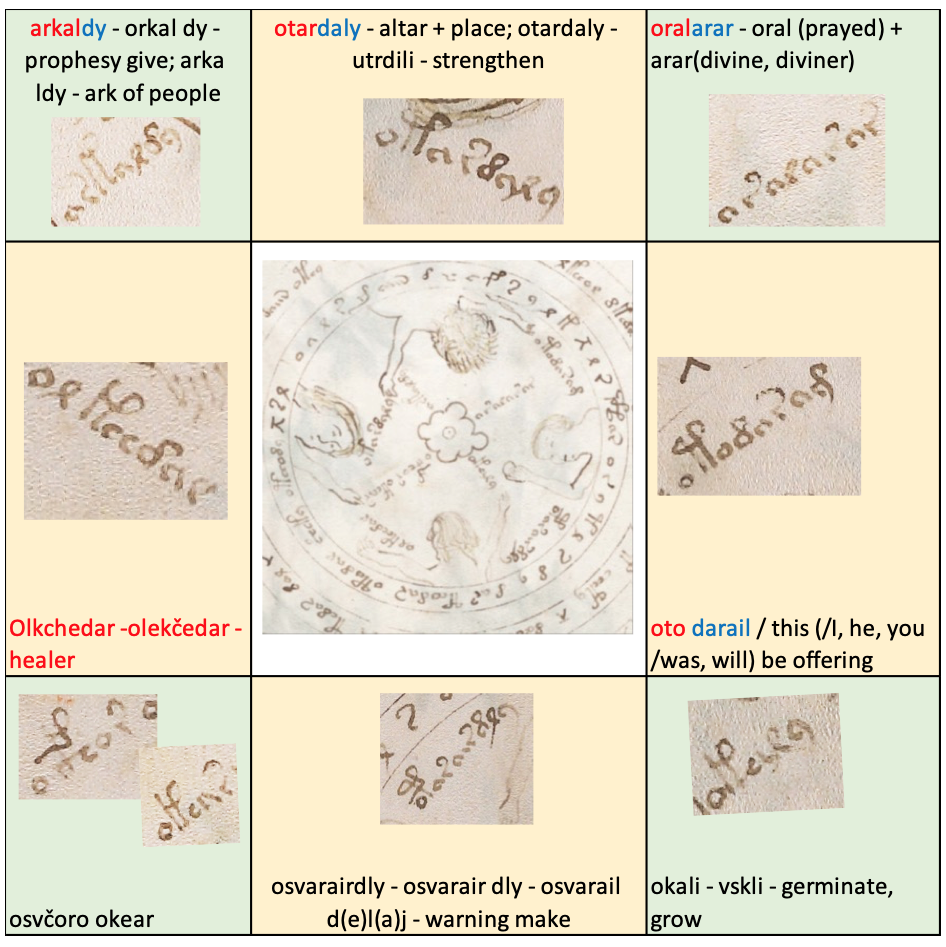

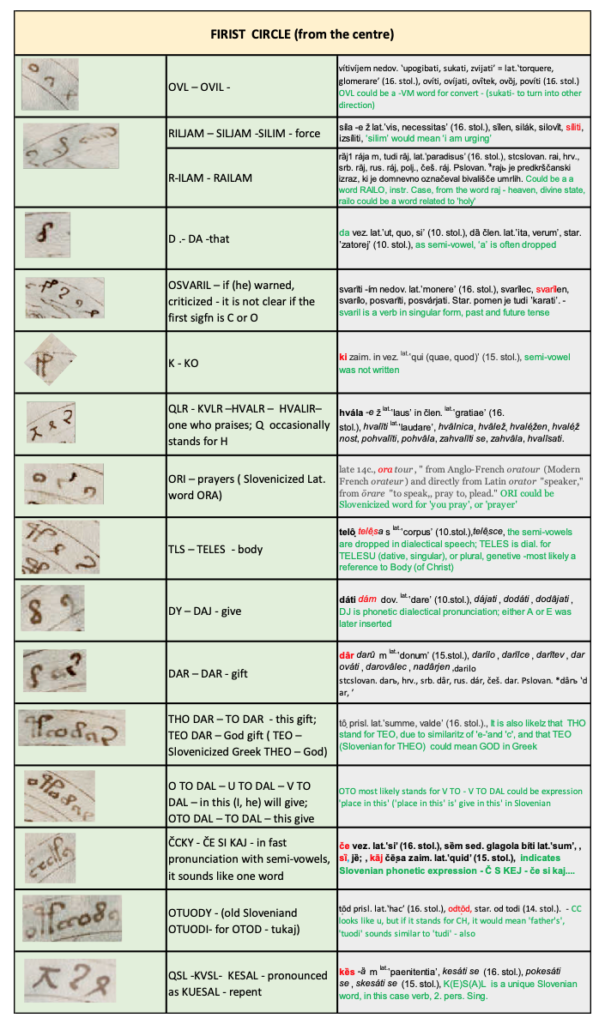

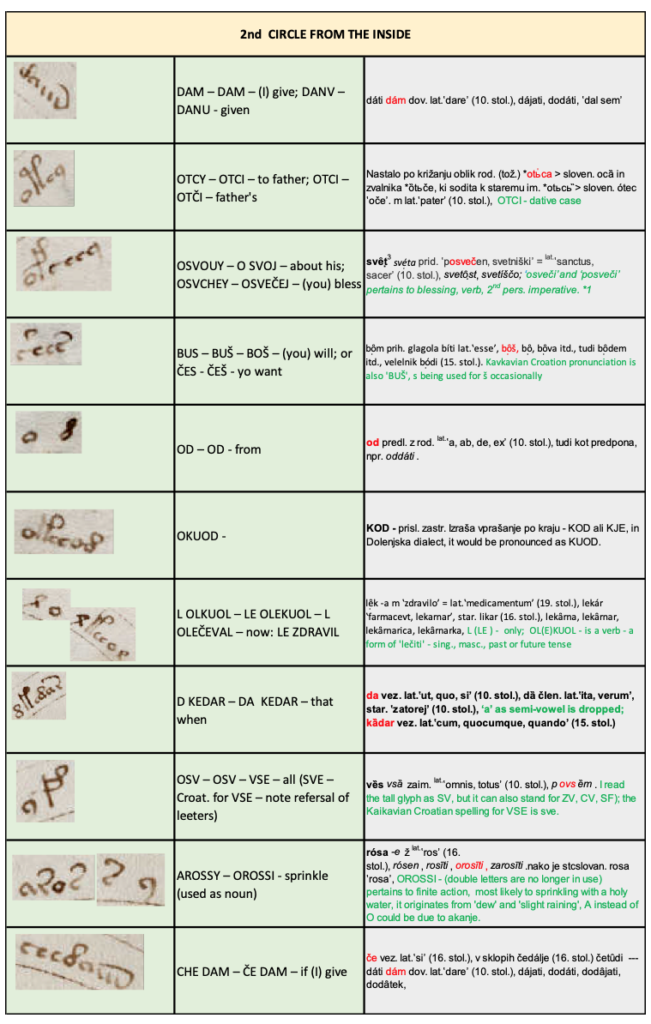

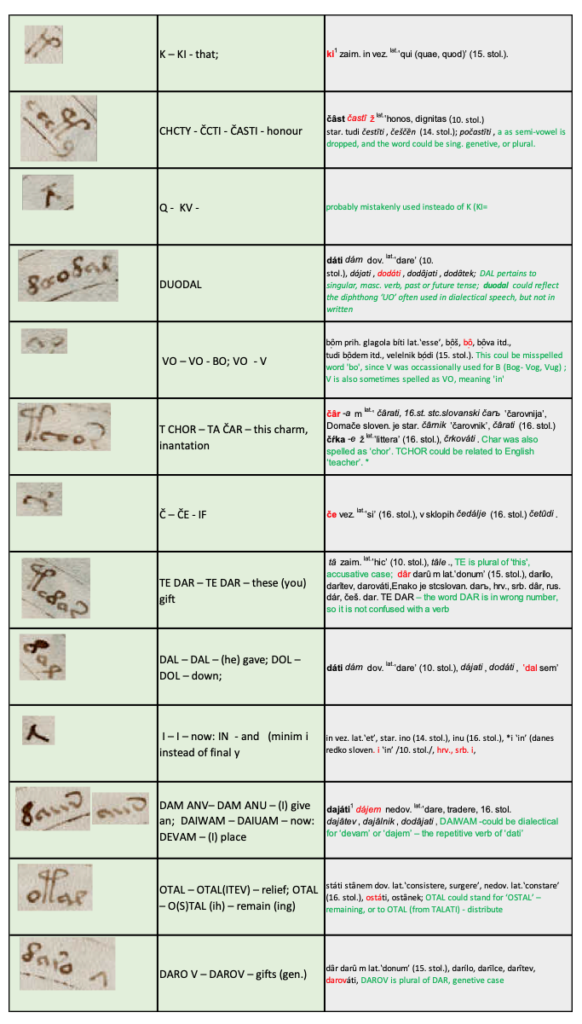

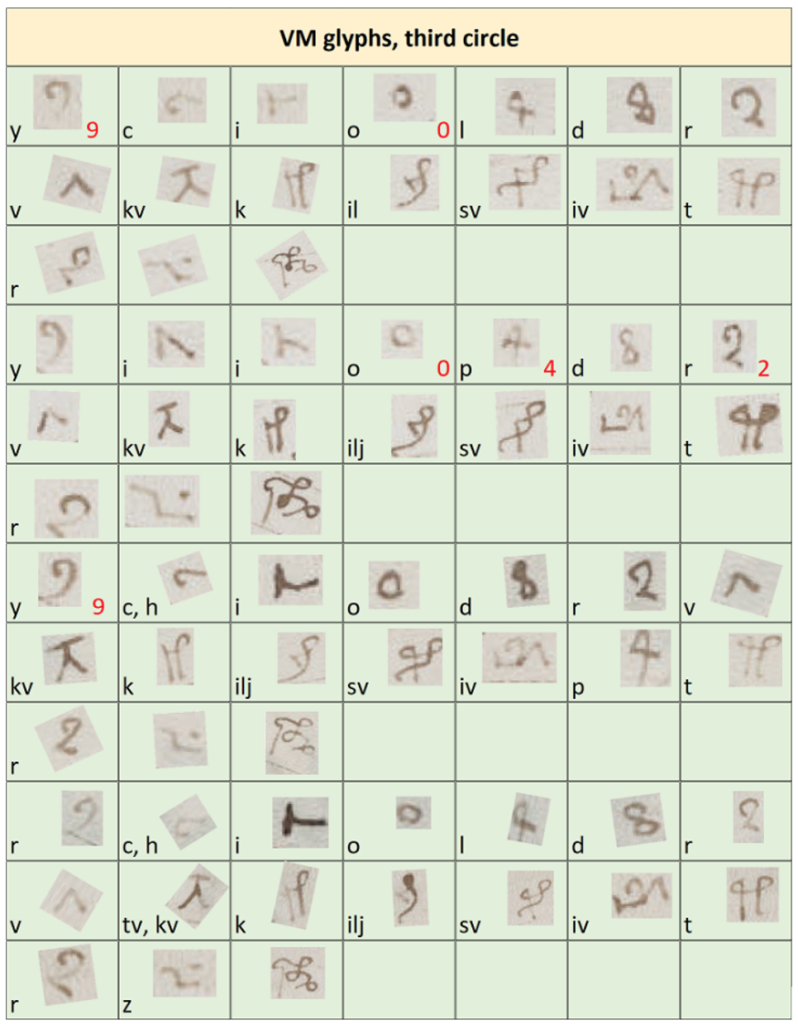

Finding this information was very helpful to me, because it enabled me to better understand the language of the VM, which contains much more Croatian words than the language of the Protestant writers 100 years later.

This serves as a proof that there was a great interest for Slovenian language in the 15th century Europe.

It is also worth noting that Croatians managed to convince the Roman popes that St. Jerome invented Glagolitza. Empire Charles IV used the same argument to promote it also in Bohemia, and for this reason, six Glagolitic priests from the island of Pašman were invited to Bohemia to revitalize the Old Church Slavonic language.

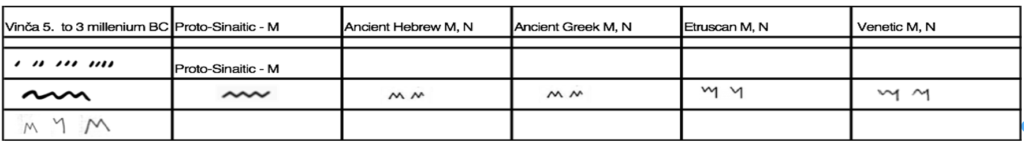

Another prevailing view among some scholars was that Sclaveni, Antes and Veneti had common origin from the ancient Veneti. This theory was introduced by Jordanes in his History of the Goths, who, like Tacitus in Germania, claimed that the Slavs are the descendants of the ancient Veneti, who lived in democracy, and were described by earlier sources, such a s Pliny the Elder, Ptolemy. This idea had sparked great interest in the 18th century, and has again resurfaced in the 20th century.

The fact remains that Slovenians in Carinthia had a special status within the Austrian Empire. Up to 1414, when Ernest the Iron became Duke of Carinthia, Carinthian dukes were installed according to the ancient Slovenian ritual in Slovenian language. His son, Frederick, who was destined for the emperor, refused to be installed according to that ancient peasant custom, when he became the Duke of Carinthia.

According to the Slavic law, Carinthians also enjoyed some privileges that allowed women to inherit property, which made them very desirable brides.

I have not been able to find out what the purpose of the formation of the Fraternity of four Slovenian Charterhouses in 1415 was, but developing written Slovenian language might not be a far-fetched idea at the time when the Counts of Celje were preparing to form a Slavic Empire.

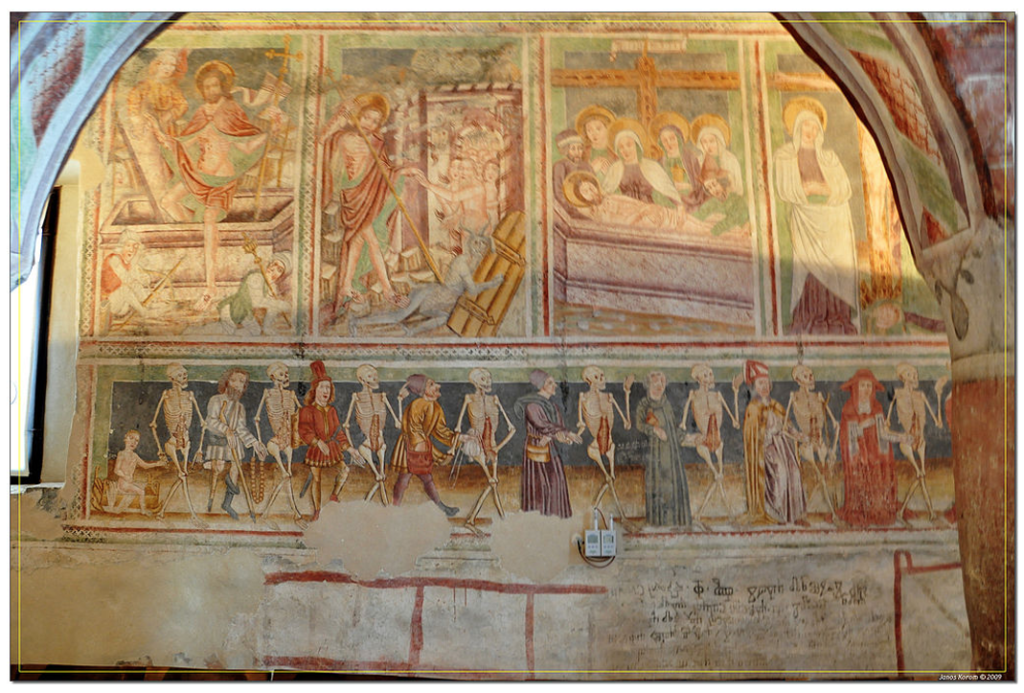

According to modern Slovenian historians, Primož Trubar was the author of the first Slovenian book, and he is credited to be the first to use expressions Slovenci and Slovenian for the people speaking Slovenian language, regardless in which political entity they lived in. The fact is, that the Carthusians used it over hundred years earlier, as attested on the document from 1415, as well as in other sources. Janez Hofler, in his book Trubarjevi ‘Lubi Slovenci’ mentions the frescoes from Strasbourg, or a miniature from the Ottonian Bible.

Because Slovenian language was not official language, Slovenian intellectuals had to write German, French, or Latin, and their national identity was almost lost, except for their Germanized Slovenian names.

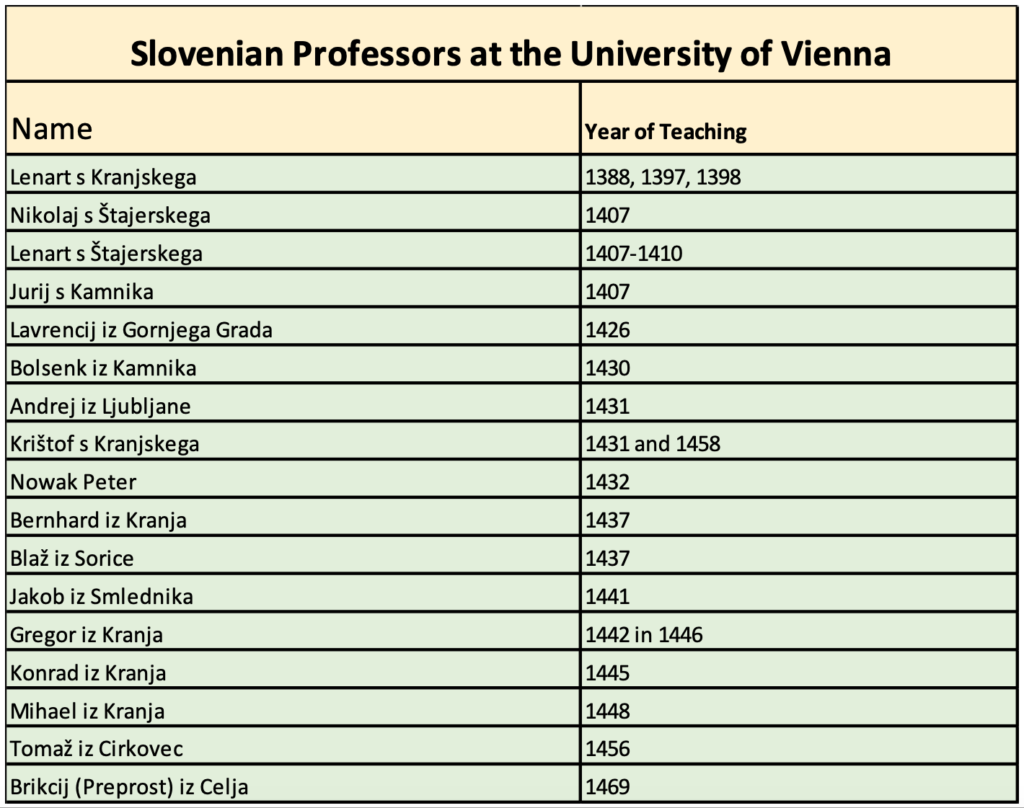

The number of Slovenian students at the Vienna university, and their position at various institutions, reflects their love of learning.

Vienna University

Nicholas Kempf started as a student at the Vienna University, and after graduating, taught for a few years, then entered the Carthusian order. Many of his friends from the University joined him. He kept in touch with the University even after he entered the monastery.

The Vienna University was founded by the Habsburg Rudolf IV in 1365, a month after he founded the town of Novo mesto (Rudolfswert in Windish Mark) and is the oldest university in the German speaking lands. The students and the faculty were divided into four nations: Austrian, Saxon, Czech and Hungarian. Slovenians from the Patriachate of Aquileia were counted among the Austrian nation. Slovenians from the regions annexed to Hungary, counted among Hungarians, and the ones for the regions annexed to the Republic of Venice, counted among Venetians. The condition for the study at Vienna University was also the use of German language.

From the Slovenian-Austrian lands, a total of 2.271 students were registered at Vienna university between 1377-1518, which represented 6 % of all students.

By the second half of the 15th century, the Vienna University experienced decline. The situation was very bad under Hungarian Mathias Corvinus (1485-1490), so that the number of students fell from a few thousand to a few hundreds. Academically, it also fell behind other universities, which embraced humanistic studies, while Vienna University was focused on scholastic.

This information gives us some inside at the study, and later, of the work environment at the university, while Kempf was there. He had openly complained against scholastic teaching, which was oppressing young creative minds, particularly poets.

Before the end of the 15th century, several new universities were founded (Trier, Freiburg, Basel, Ingolstadt, Mainz, Tubingen) where the spirit of humanism and classical literature prevailed over dry scholastic. Slovenian academic Brikcij Preprost (Briccius Preprost) from Celje was credited for reforming the Vienna University (it is most likely that Briccius was influenced by Nicholas Kempf, who is regarded as one of the great humanist and monastic reformer of his time). Kempf would have been prior at Jurklošter (within walking distance from Celje) Charterhouse while Brikcij was preparing for the university study.

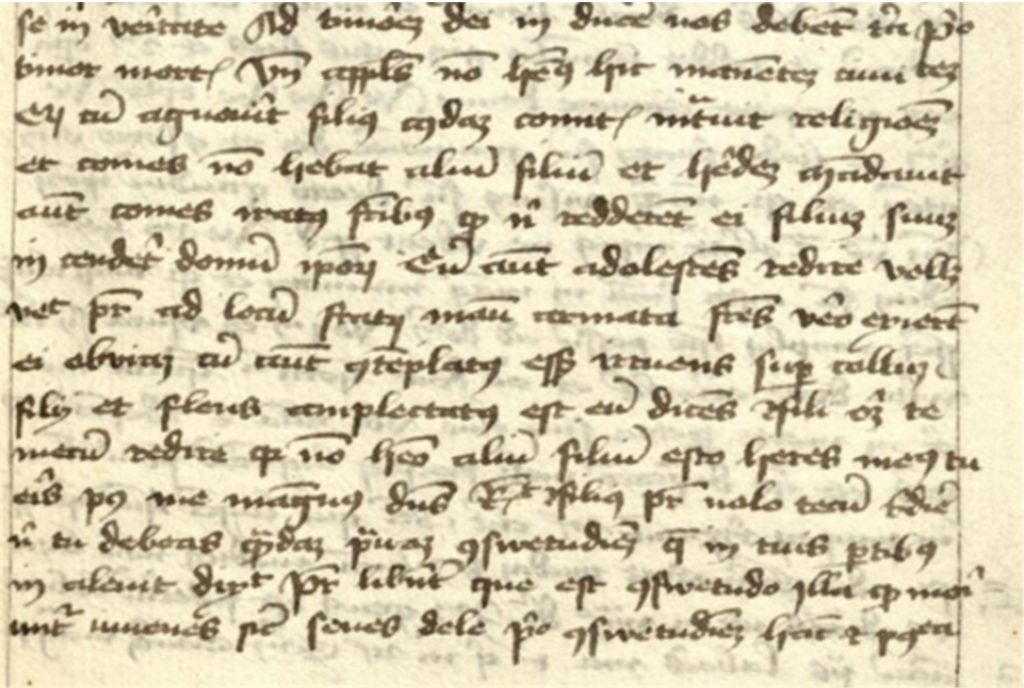

Nicholas Kempf was as critical of Vienna University scholastic teaching as was Preprost who was a faculty member years after Kempf left. After the Basel council was suppressed, the conservatism prevailed, which was in part the reason Kempf left the University and entered the Carthusian order. He adhered to the Church Reforms introduced by the Council of Basel. He seems to be supportive of Hussites, although he did not fully agree with them, because Jan Hus interpreted the biblical writing literally, not symbolically. Kampf remained true to his convictions, unlike Piccolomini, who was humanist and supporter of Basel Council at first, but switched his loyalty and became a bishop of Trieste, then a cardinal and eventually a pope, who installed his own nephew as his successor. As Pope Pius II, he sent Crusades to suppress Hussite war.

Because of the spread of Protestantism, renounced as heretical by the Catholic Church, most Slovenian students opted for study on German universities. First Slovenian books were printed in Tubingen. To stop the spread of Protestantism, the Vienna University would not even accept students, nor professors, from the lands where Protestantism was spread.

Among the most famous Slovenian contemporaries of Nicholas Kempf, two individuals from Celje should be mentioned.

Slovenian Bernard Perger was one of the most distinguished mid-15th century academics in Vienna. He registered at Vienna university in 1459, studied philosophy and until 1481, lectured geometry, mathematics, astronomy, and classical literature. He also studied medicine and Law. In 1471, he became rector of the Vienna University. He also taught Latin Grammar and wrote a Grammar book (Grammatica nova) Venetiis, 1479, in association with Nikolay from Novo mesto and Preprost from Celje. Between 1492 and 1501, Perger was the imperial superintendent at the University (representative of Emperor Frederick III, and later Maximilian I).

Tomaž Prelokar, also known as Thomas de Cilia, Thomas Berlower or Thomas Prelager, was born around 1430 most likely in a lower class family. He attended art faculty at the Vienna University (after Kempf left, and after Kempf spent several years as a prior at nearby Jurklošter).

Prelokar studied at the Arts Faculty and became Magister. Afterwards, he went to Padua, Italy, where he became Doctor of Law in 1466. In 1470, he was employed at the court of Emperor Frederick III, where he became Emperor’s trusted secretary and teacher of his son, Maximillian who was destined to succeed Frederick. It is known fact that the Emperor spoke Slovenian. Thomas was first humanist at the court of the German Emperor, which became the gathering place of humanistic intellectuals. Eventually, he became a bishop of Constance, and prince of the Holy Roman Empire. He died in 1496.

According to Slovenian sources from the 19th century, Thomas Prelokar wrote Slovenian grammar book and Slovenian dictionary.

Conclusion

We tend to think of Carthusians as monks spending their time in solitude. While this might be the case for the monks, a prior had to communicate with the monks and with the outside word. He also had to teach the monks and lay brothers how to read and write. He attended court sessions, lectured at the universities. This is how I imagine the life of Nicholas Kempf who is known to keep in touch with the Vienna University, its former students and fellow faculty members. This would give him plenty of opportunities to meet at least some professors from the present day Štajerska, if he did not meet them before.

Because Perger was much younger than Kampf, he most likely did not meet Kempf as a student at Vienna. It is possible that he met him, since they had common interest in philosophy, and since Kempf kept in touch with the university. Perger wrote his Latin Grammar book with the help of Preprost, who also came from Styria, and Nicholas from Novo mesto. Preprost and Perger were both from the vicinity of Celje, so they could have been prepared for the university study by Kempf at the Jurklošter Charterhouse, which was within a walking distance of their homes. The monasteries were the places where young boys were prepared for the university studies, for which the knowledge of Latin and German was required.

I was not able to get any information about Nikolaj from Novo mesto. At the time, Novo mesto was a small newly founded town, some 20 kilometres from Charterhouse Pleterje. It is possible that Nicholas Kempf identified himself as Nicholas from Rudolfswert, since Pleterje Charterhouse was within a walking distance from Novo mesto, and perhaps not that well known.

Brikcij Preprost (Briccius Preprost de Cilia) was born around 1440 and was registered at the Art Faculty at the Vienna University in 1457. Eventually, he became the dean of Arts Faculty. It looks like he encountered some problems there when in 1486, he refused to testify against his countryman, George from Cilli, a medical doctor who was accused of heretical writing by the University.

Heretical writing could be anything the Roman Church did not approve, since by then, any ideas prior accepted by the Basel Council, were no longer acceptable, after Frederic III allied with the Roman pope Eugene. Kempf was a Catholic, but he still adhered to the ideas of the Basel Council.

Since Nicholas Kempf is also mentioned by Martin for his contribution to Latin grammar at Vienna University, we can safely assume that Kempf, Perger and Praprost knew each other, and that they work at least on one project together.

Perger was also known as astrologer and he might contribute some ideas for the astronomical pages in the VM.

Another Slovenian, Kempf might have met, was Thomas Prelokar from Celje.

It is less likely that Thomas was the author of the VM, because that would place its creation after 1470. This would be too far outside the date determined by the carbon dating, and because the book is not arranged as a grammar book, nor as a dictionary, but rather the mixture of different things, alluding to be a personal book of a poet, who also had other interests, but most likely the spiritual notes and perhaps the ideas for sermons or for teaching Slovenian language.

Assuming that the author of the VM was Nicholas Kempf, who was known for promoting vernacular language in liturgy, this would explain why the first Slovenian books – a grammar and a dictionary were written by Thomas of Celje, and some 70 years later by Trubar, native of Dolenjska region.

It is possible that there was greater effort made for the learning and use of Slovenian language, however when the Catholic Church failed to accept the reforms to introduce the vernacular languages, the use of Slovenian books for liturgy was probably regarded as Protestant. This could also explain why only five out of 30 books written by Nicholas Kempf have been preserved (in copies only), and why even those saved, were never translated into Slovenian language. Some of his ideas had to wait 600 years to be accepted by the Catholic Church at the Second Vatican Council. However, like other Protestant literature, his ideas were transmitted underground, by way of literature, in symbolic language that only other like-minded mystical artists understood and transmitted in culturally acceptable forms.

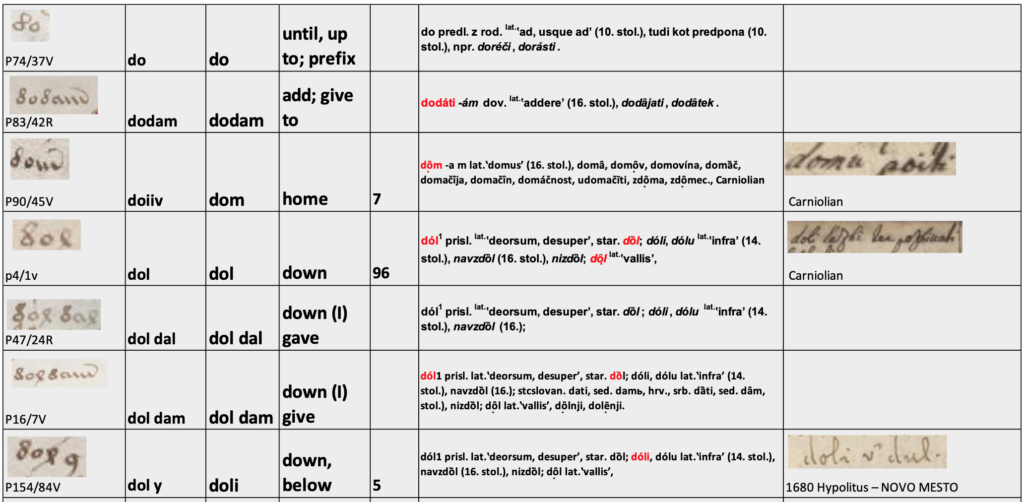

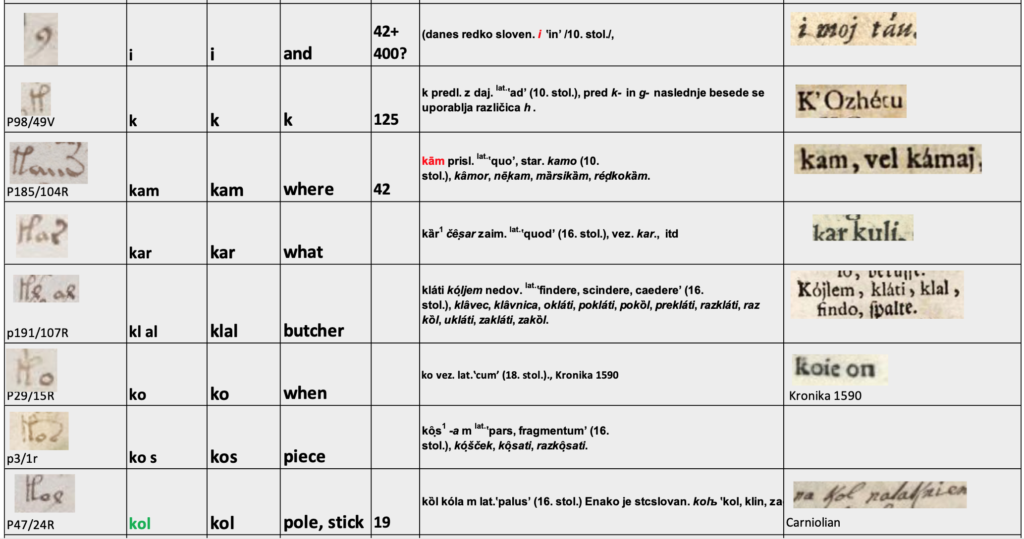

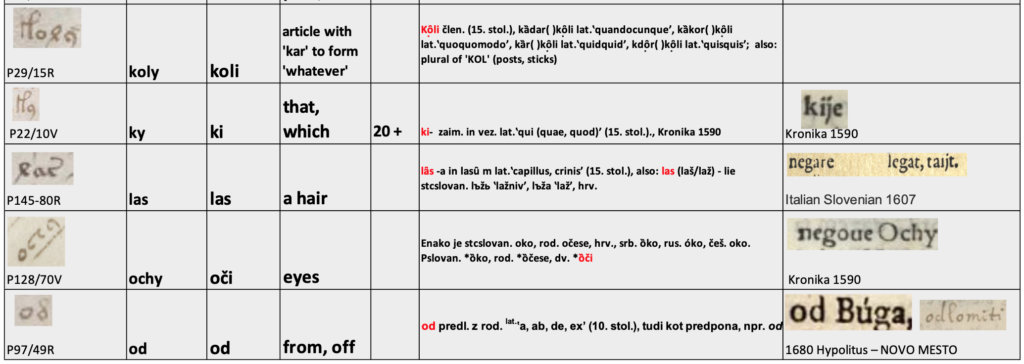

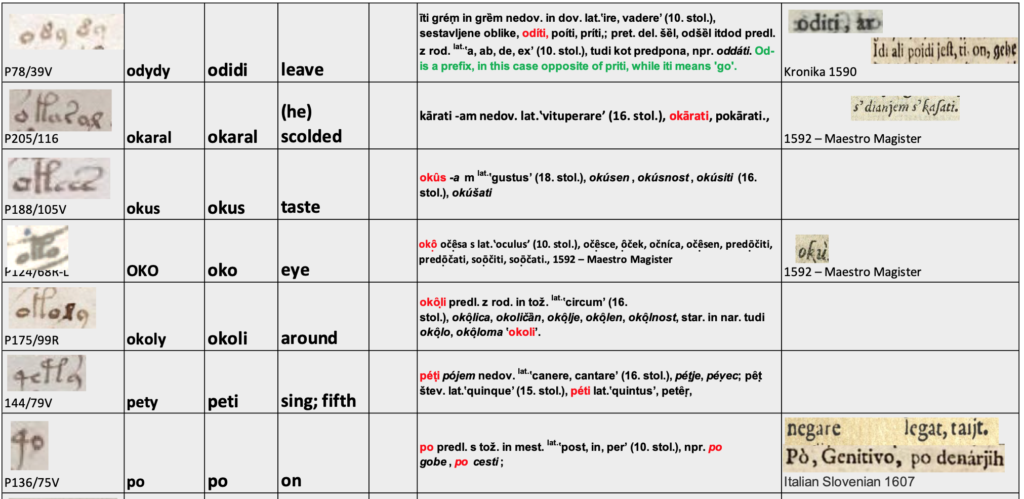

Slovenian or Carniolan language

Although I believe the VM is written in Slovenian language of the 15th century, this is hard to accept by the contemporary Slovenian scholars, who had already determined that the first book written in Slovenian language was Trubar’s Cathehismus and Abecedarium from 1550. This is understandable, because the internet enabled much more material to be available, not only to academics, but to amateurs as well. If there were any books perserved, they were lost in foreing libraries. Slovenians are very excited about the few Slovenian words used by German poet Ulrich von Liechtenstein in the 13th century. Recently, a discovery of the numbers of one to ten, written in Slovenian in a 13th century German manuscript, caused great sensation.

Alternative theories and explanations are offered as the history is being re-examined in view of the wealth of information, offered on line in original languages and in English.

Unlike the Protestant writers of the mid-16th century, who dedicated their book to Slovenians in order that all those who spoke different Slovenian dialects (Carinthian, Carniolan, Istrian, Slovenian and Bezjak) can read them, the VM had no introduction, no dedication, and no name of its author.

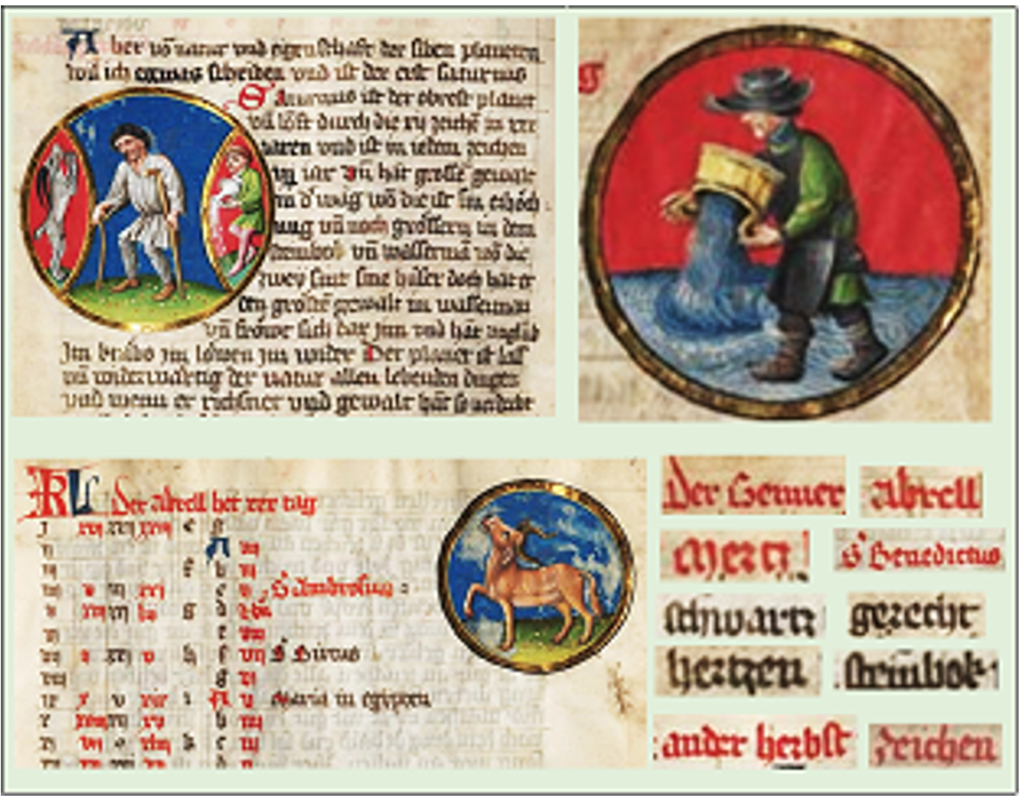

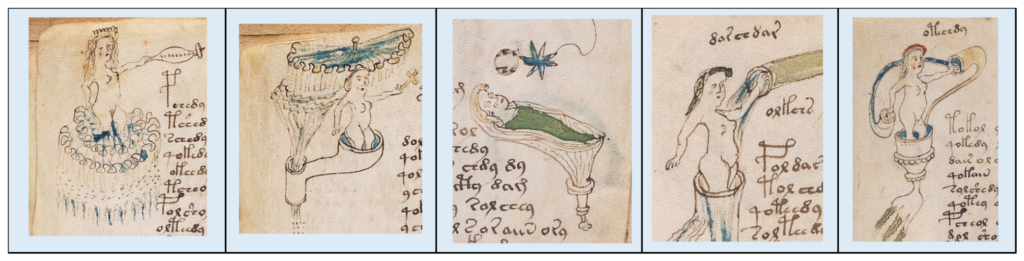

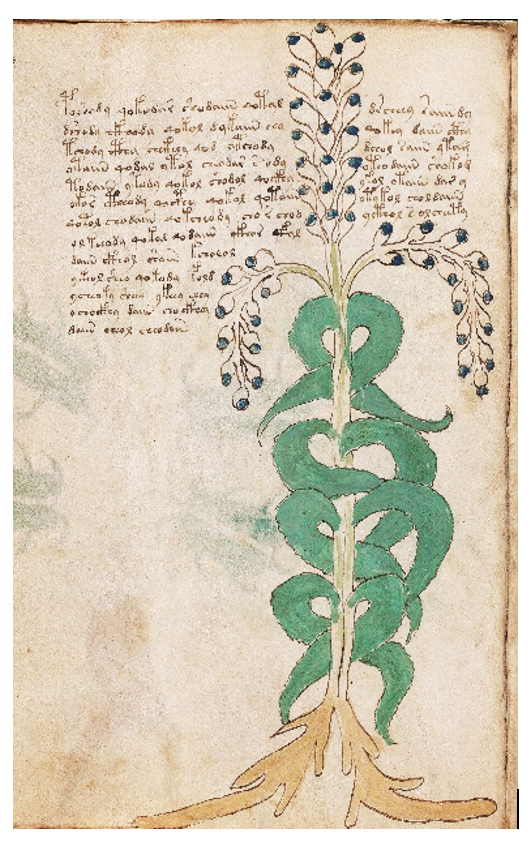

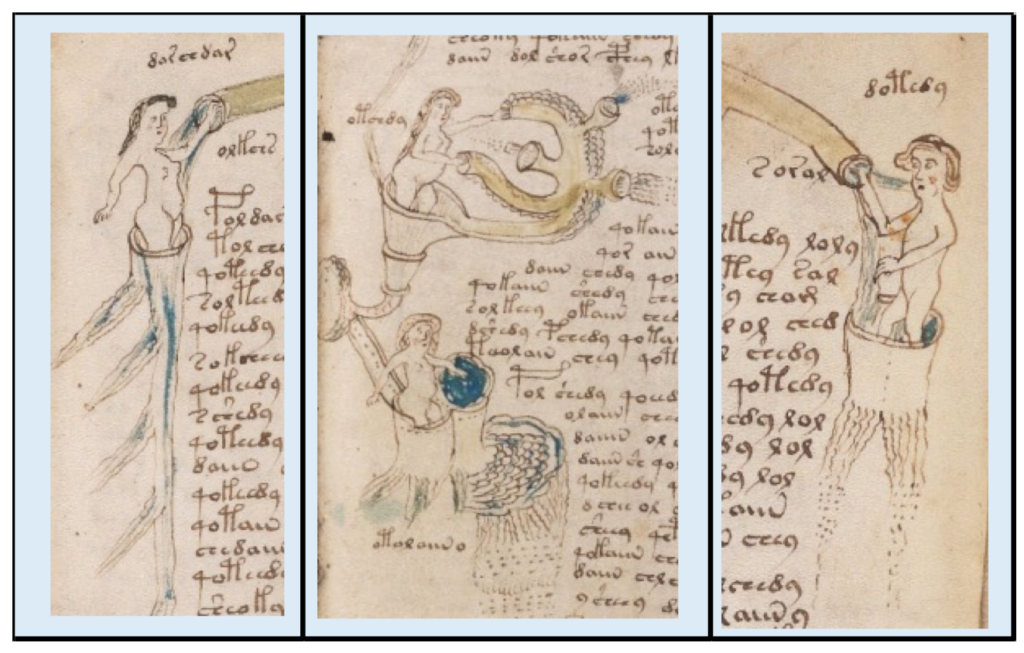

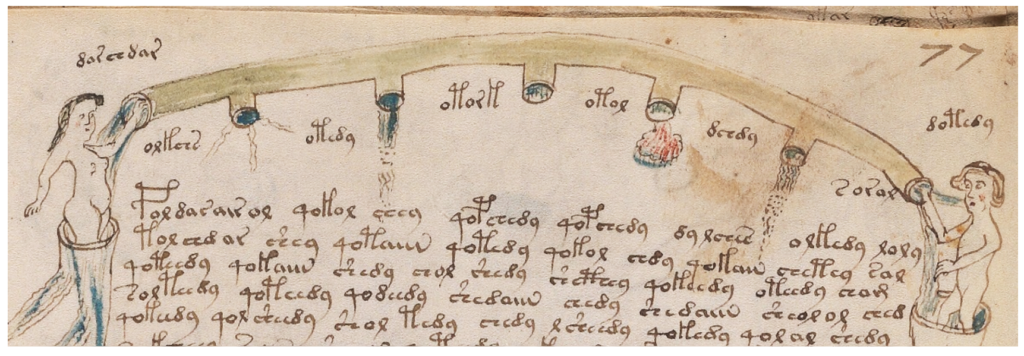

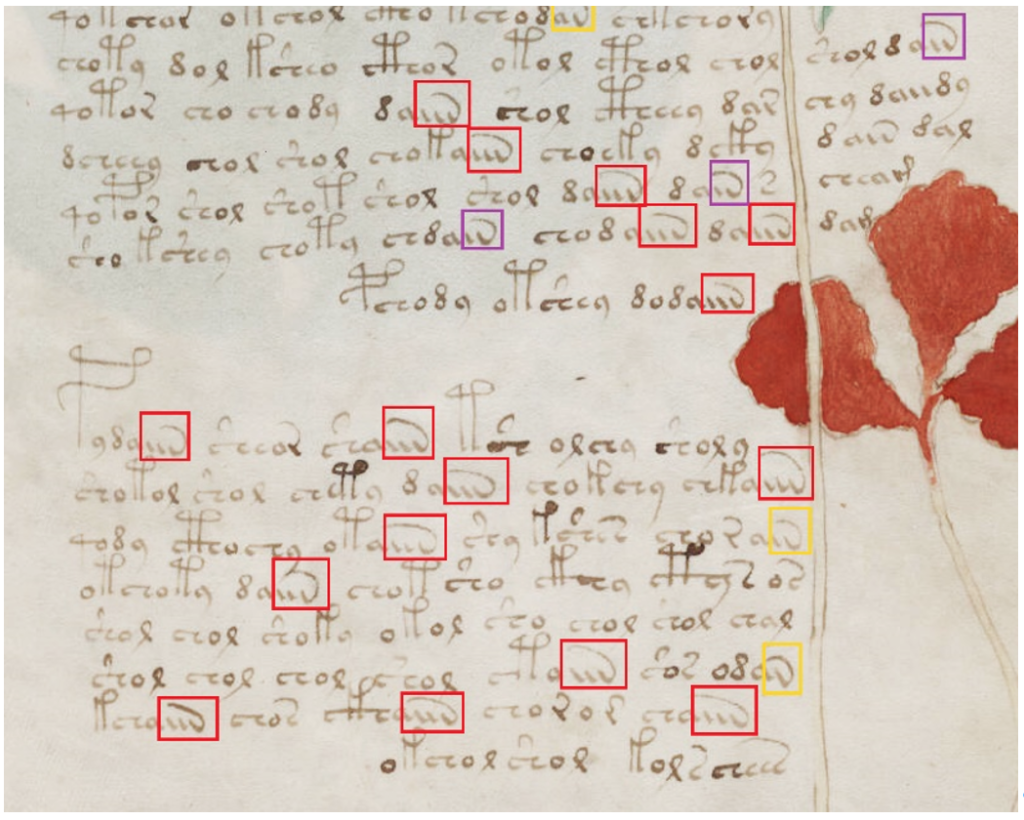

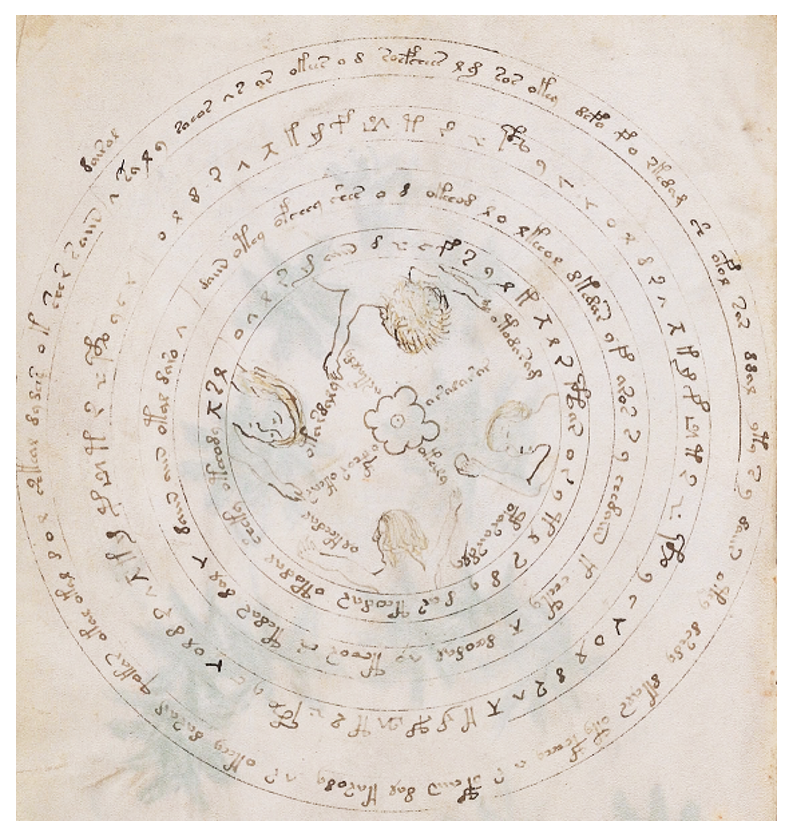

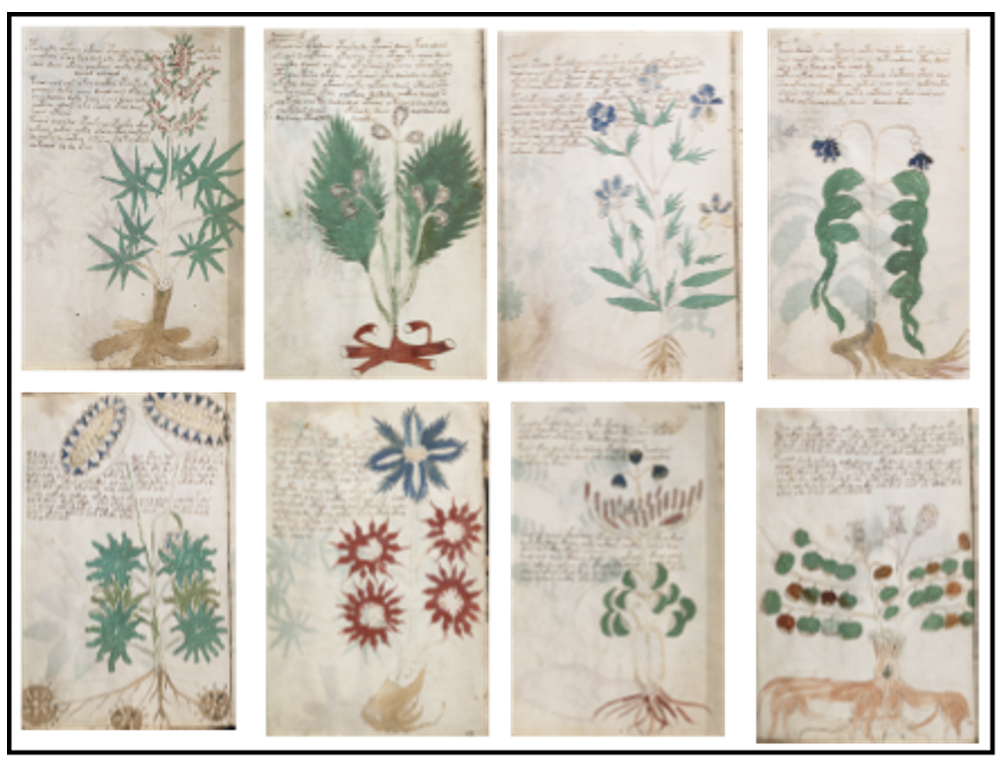

The VM is different from other medieval manuscripts, although it shows some likeness to the German genre of Medical Housebuchs. It included the pages with zodiac signs, but it does not include calendars, nor the pictures of saints. The largest part is devoted to flowers, yet the flowers look weird and the text next to the individual flowers look like poems.

I believe the VM is written for a personal interest, for teaching oneself (and perhaps the fellow monks) Slovenian language and Slovenian writing. Since labels (individual words) have no Latin or German translation, it is most likely that the book was meant for somebody who knew how to speak and could recognize the written words. This means that the author had created pages of written words as a teaching aid for spelling and grammar. The full pages of text could be notes for sermons, personal reflections, or various instructions.

The pictures, although of inferior quality, could be the expression of authors’ philosophy, expressed mostly in floral symbolism, or in abstract art, to satisfy author’s inner need for expression of his higher wisdom, something he could not share with people who hardly new how to read basic words.

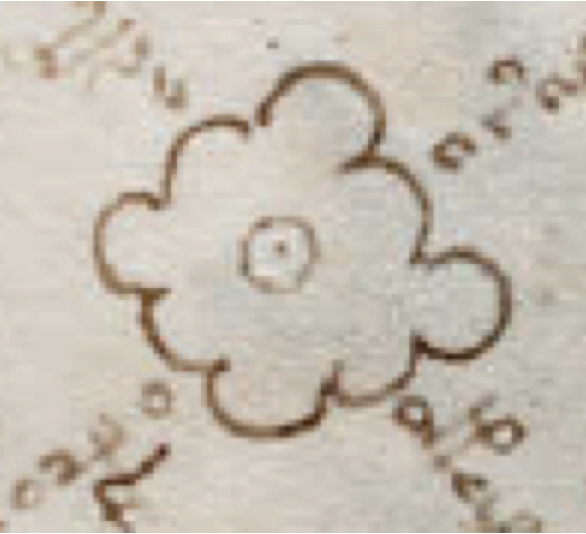

The word ‘flower’ was used by humanistic writers to mean the superlative of phylosophical sayings in the book of Rosary of Philosophers (12th century). The work of Picolo of Mirendolo was regarded ‘flowers of heresy’ by the pope. In Slovenian language, the symbolism of flower goes even further; the best of home made brandy is called ‘cvet’ (flower, blossom), the youth is called ‘cvet mladosti’ (flower of youth). In general, the word ‘flower’ was used for ‘flowers’ and for ‘poetry’.

I noticed the high frequency of the word ‘(r)oza in the VM. At times, it is hard to tell when it is used in a real or in symbolic sense.

Main sources:

Ožinger, Anton: Študenti iz slovenskih dežel na dunajski univerzi v poznem srednjem veku (1365-1518)

Prosen, Marijan: Astronom iz Slovenskih Goric, 1993

Höfler, Janez: Trubarjevi »Lubi Slovenci« ali Slovenija pred 650 leti v Strasbourgu, 2009